Moral relativism in Scott Pilgrim

The difference between a fun-but-forgettable book and a great book is that a great book resolves some struggle in the author’s heart. It might not have a happy answer or an easy solution, but it takes a source of confusion and pain in the author’s world, and takes a stand about what it is or what it means.

Take The Great Gatsby for instance. Each character in the book arguably represents a different response to the crisis that F. Scott Fitzgerald saw in the world around him, namely that his contemporaries had lost faith in enlightenment values following World War I. He believed they were living empty lives of conspicuous consumption, hurting themselves and others. In writing The Great Gatsby, Fitzgerald transformed that feeling from one man’s impression into a cultural truth, giving it iconic weight that continues to have force eighty-seven years later.

Tom Buchanan is a character in the book, a former star college football player who’s now rich, powerful, and morally lost. Fitzgerald writes, “Tom would drift on forever seeking, a little wistfully, for the dramatic turbulence of some irrecoverable football game.” Without rules, goal posts, and an opposing team, Tom doesn’t know what to do with himself. He acquires trophy horses, trophy cars, and a trophy wife, but he’s still dissatisfied.

The protagonist of the Scott Pilgrim graphic novels, by Bryan Lee O’Malley, is sort of a Tom Buchanan for our generation. He’s a hipster everyman, or at least, an every-man-child. Funded by his wealthy parents and roommate,  he’s unemployed and spends his time sleeping, playing video games, and practicing with his indie rock band. Like Tom, Scott yearns for a remembered clarity of purpose, although in his case, it’s memories of playing games like Bomberman, Sonic the Hedgehog, or The Legend of Zelda.

he’s unemployed and spends his time sleeping, playing video games, and practicing with his indie rock band. Like Tom, Scott yearns for a remembered clarity of purpose, although in his case, it’s memories of playing games like Bomberman, Sonic the Hedgehog, or The Legend of Zelda.

Scott Pilgrim is about Scott’s quest to grow up, in a world that’s okay with him staying a child. It’s about what it means to be an adult in a post-modern society, one where relativism, self-reference, and irony have eroded faith in any kind of external standards or norms. I would argue that Scott Pilgrim is significant because it goes beyond post-modernism by asserting that there is an answer to “okay, so then what?” O’Malley takes a stand that even in our fractured, post-everything, been-there-done-that world, there’s still an “up” to grow into.

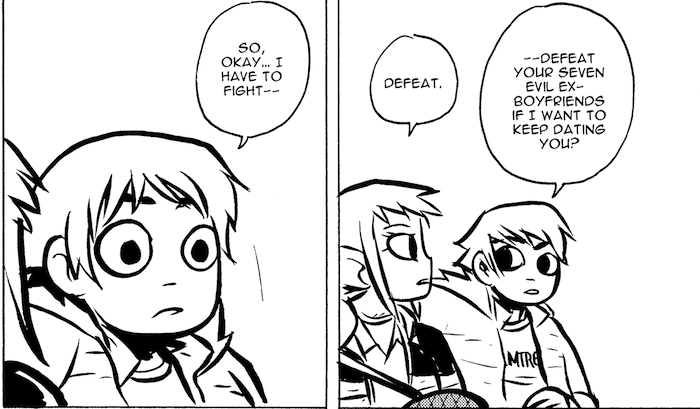

In contrast to Tom’s football games, which never become more than nostalgia for him, Scott takes his video games and runs with them. The central conceit of the Scott Pilgrim novels is that the ambiguous, open-ended process of trying to achieve a mature self-identity (proxied by the challenge of getting into a healthy relationship with a girlfriend) plays out in Scott’s mind as a linear-video game-style adventure. Like Mario pursuing Princess Peach, Scott has to defeat a series of bosses to date Ramona, the girl of his dreams::

This challenge — defeating Ramona’s evil ex-boyfriends — forms the narrative arc of the six Scott Pilgrim novels. Over the course of the books, Scott defeats the boyfriends one by one, meanwhile dating Ramona and interacting with his circle of friends.

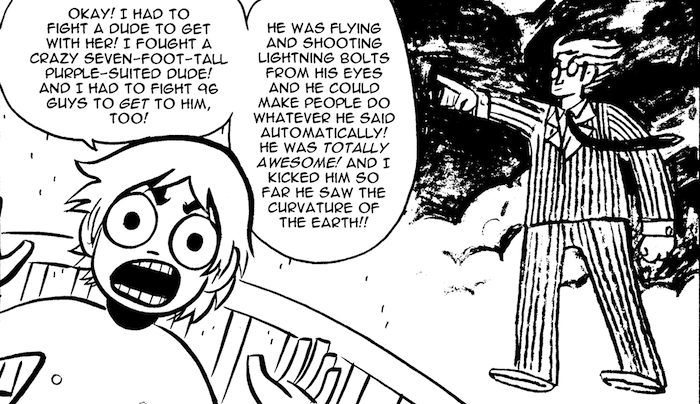

Scott Pilgrim makes no bones about being set in an imagined reality. Woven between true-to-life depictions of the Toronto hipster scene are completely over-the-top sequences such as a kung fu battle in a public library, a katana fight in an urban backyard, vegans with psychic powers, alternative dimensions, and the destruction of various Toronto landmarks.

Scott Pilgrim makes no bones about being set in an imagined reality. Woven between true-to-life depictions of the Toronto hipster scene are completely over-the-top sequences such as a kung fu battle in a public library, a katana fight in an urban backyard, vegans with psychic powers, alternative dimensions, and the destruction of various Toronto landmarks.

O’Malley mixes the surreal and the mundane with brazen ingenuousness. For instance, Ramona’s ability to literally show up in Scott’s dreams is explained like so:

Ramona: “No, no, it’s… it’s just, like, this really convenient subspace highway happens to go through your head. It’s like three miles in fifteen seconds, and through your–”

Scott: “Hold on, what? Subspace? Highways?”

Ramona: “Yeah, what? Huh?”

Scott: “You’re– talking crazy talk?”

Ramona: “Is this something they don’t teach in Canadian schools?”

Scott: “Can you elaborate?”

[…]

Ramona: “You guys probably just don’t know about them in Canada. I was wondering why they were always empty up here.”

Scott: “So… um, I guess you’re American?”

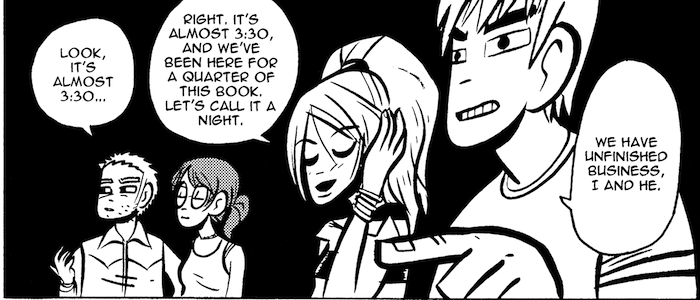

Scott Pilgrim Scott Pilgrim is highly self-aware. It doesn’t break the fourth wall; it melts it away. To the characters, the fact that they’re in a story is no big deal. For instance, in this scene, Envy, one of Scott’s own exes, suggests postponing Scott’s fight with the third evil ex-boyfriend:

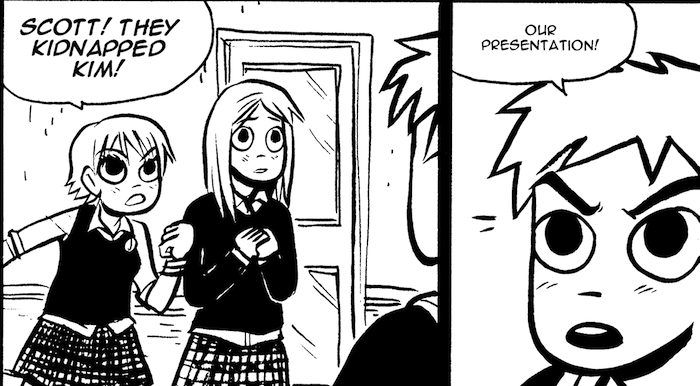

Earlier in the series, when Scott fills his bandmate (and former girlfriend) Kim in on his quest, her reaction is one of incredulity:

Scott: “So I have to train, by watching these movies, and then go find him and fight him.”

(long pause)

Kim: What?!”

Scott: “It’s a long story, okay?? Read the book sometime.”

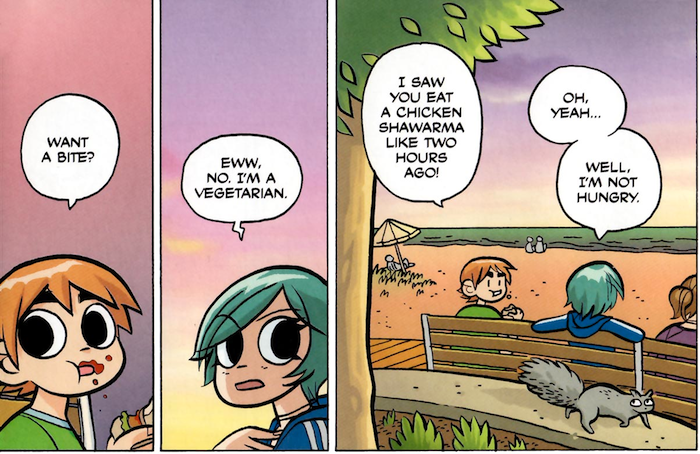

The fascinating thing about the graphic novels, though, is that while the formal elements are completely artificial, the content — i.e., the characters and their inner journeys — feels real. Scott and Ramona awkwardly date, they fall in love, fight, split, and get back together as they learn to be a couple, while at the same time their friends have their own challenges and breakthroughs. Mixed in with the surreal plot points are ordinary slice-of-life scenes where the characters do things like grabbing burgers and building bonfires on the beach:

Whereas many works have a veneer of reality covering their artificiality, Scott Pilgrim has a veneer of artificiality that covers a deeply organic universe.

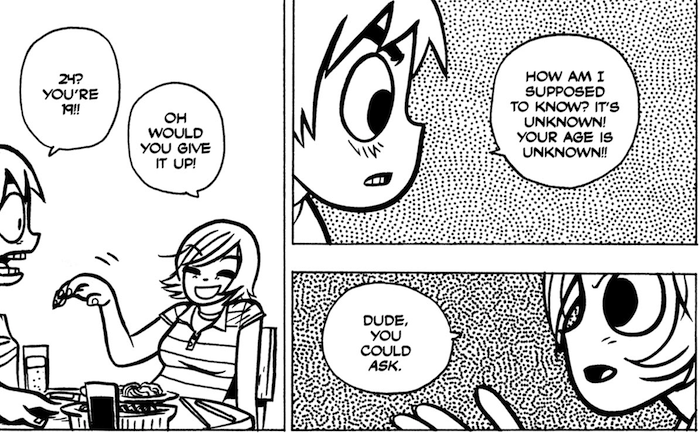

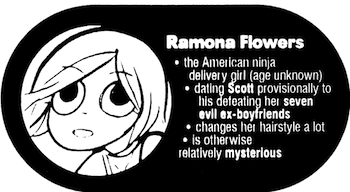

One of the ways O’Malley accomplishes this is by filtering the narration through the mind of his protagonist, who as it turns out is an unreliable narrator. While the more fantastical elements of the plot are taken at face-value — there’s no “Scott’s making this all up and is actually insane” Hollywood twist — many of the minor plot points, especially related to the evolution of Scott’s friends, appear largely as subtext. The perspective we get of the universe (reinforced by narrator-voice messages such as the one to the left) is Scott’s perspective. At one point, for instance, Ramona challenges Scott on how well he actually knows her, and he insists that (in his reality) “her age is unknown”:

One of the ways O’Malley accomplishes this is by filtering the narration through the mind of his protagonist, who as it turns out is an unreliable narrator. While the more fantastical elements of the plot are taken at face-value — there’s no “Scott’s making this all up and is actually insane” Hollywood twist — many of the minor plot points, especially related to the evolution of Scott’s friends, appear largely as subtext. The perspective we get of the universe (reinforced by narrator-voice messages such as the one to the left) is Scott’s perspective. At one point, for instance, Ramona challenges Scott on how well he actually knows her, and he insists that (in his reality) “her age is unknown”:

In Scott’s low moments, he evinces the attitude that his perspective is the only one that matters. For instance, when confronting Gideon, the final ex-boyfriend and founder of the League of Evil Exes, Scott declares “I don’t even want to fight you! The secondary characters made me do it!”

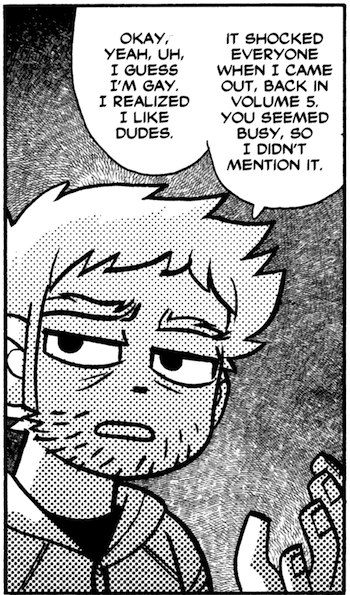

The “secondary characters”, however, have narratives of their own. For instance, Scott’s bandmate Stephen comes out as gay, despite starting the novels with a girlfriend. There are sprinkled references to this development throughout the last three volumes, but it’s not til the very end of the series that Scott finds out about it (and we as the readers are informed directly), even though everyone else in the books knew it was going on.

The “secondary characters”, however, have narratives of their own. For instance, Scott’s bandmate Stephen comes out as gay, despite starting the novels with a girlfriend. There are sprinkled references to this development throughout the last three volumes, but it’s not til the very end of the series that Scott finds out about it (and we as the readers are informed directly), even though everyone else in the books knew it was going on.

The net effect of Scott’s unreliable narration is both post-modern and (and I apologize for this, but how else is there to put it) post-post-modern. The subversion of the authorial viewpoint is a classic move of post-modernism: it breaks the illusion of an omniscient narrator describing an objective reality, and suggests instead that the meaning of the text is constructed. But the way O’Malley does it actually reinforces the authenticity of the narrative universe. Scott Pilgrim, unlike a classic modernist novel, doesn’t take itself seriously to begin with. The whole thing is tongue-in-cheek, and the fact that it’s not real is out in the open. So when O’Malley shows that the narrative viewpoint subtly excludes or diminishes the stories of the non-Scott characters, the effect is to make things feel more real, because there’s the implication that there’s an entire world outside the narrow aperture we’ve been permitted to gaze through. What we get is an open-ended world, one that clearly can’t be taken at face value, but that seems to have a life of its own nonetheless.

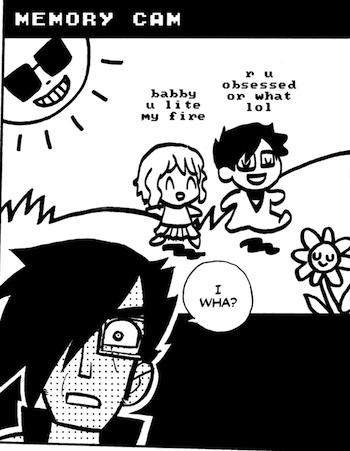

One of the important motifs in Scott Pilgrim is memory. Scott’s memory is unreliable, and we slowly discover of the course of the books that this is one of his most important character flaws. For instance, in high school, prior to the events of the books, Scott dated his bandmate Kim after beating up her then-boyfriend. The story is told three times, in volumes 2, 3 & 6. The first repetition is presented as a (factual) flashback:

In the second, Scott first denies and then exaggerates the story to Ramona in response to her probing:

Then finally Kim reminds Scott of her version of events:

Scott’s unreliable memory is more than just a critique of narrative structure. It takes on moral significance in the evolution of the storyline. To progress towards his goals, Scott has to stop forgetting his mistakes and distorting his version of reality to fit his self-image, and instead accept his past and himself for who he is. As he says to Kim before his final confrontation with Gideon over Ramona:

Scott: “I remember everything. I don’t deserve to get her back”

Kim: “So fight for her. Earn her back.”

What we discover in the course of Scott’s fight with Gideon is that Gideon and Scott share the same character flaw of smoothing over their messy pasts. Earlier in the book, when Scott’s ex Envy asks him: “Do you remember anything?”, Scott reflects:

Then in the final fight, Ramona asks Gideon why he even cares about fighting over her, given that he never really wanted her until she left him. Gideon also has a flashback (to the right).

Then in the final fight, Ramona asks Gideon why he even cares about fighting over her, given that he never really wanted her until she left him. Gideon also has a flashback (to the right).

The difference between Scott and Gideon ultimately comes down to the choice they make when confronted with their past. Scott, although initially resistant, is willing to admit painful versions of events back into his recollection. Gideon instead declares “Insolent whore! Don’t you sully my memories!” and tries to slice Ramona to bits with a sword. Scott, when forced to choose between his self-conception and a friend, picks the friend; Gideon picks his self-conception.

Although the confrontation between Scott and his various adversaries is superficially depicted as physical, the actual combat acts as a proxy for Scott’s moral growth. Scott only gains the moral authority to judge and thereby defeat Gideon once he recognizes in Gideon his own shortcomings. At the beginning of the fight, Scott is overmatched and on the defensive, but near the end he achieves an epiphany:

Scott: “I think I understand you, man.”

Scott: “…And now I have to kill you.”

Although in Scott Pilgrim‘s universe, the self is uncertain and self-knowledge is relativistic, nevertheless there’s room for real progress towards authenticity. Scott is a different character at the end of the books than at the beginning, and he grows by being willing to embrace the parts of himself that he doesn’t like. Gideon, in contrast, is “evil” because he refuses to accept his own dark side.

The framing structure of Scott Pilgrim, the seven successive fights, is patently artificial. It’s real life flattened into a video game, and at face value it’s absurd that the fundamental ambiguity of Scott’s maturing process can be represented through such a linear medium. Yet, throughout the progression of the story, Scott experiences genuine moral growth. In part, this tension between artificial form and genuine content is resolved by not taking the form too seriously. For instance, at one point, Scott and Ramona decide to skip out on one of Scott’s scheduled confrontations:

Scott: “Are you sure it’ll be okay?”

Ramona: “Dude, come on. We’re shirking duties randomly made up by people who hate us.”

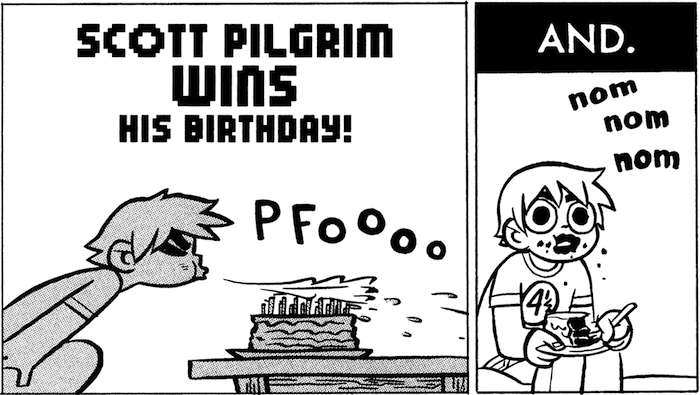

As in most video games, the series’ story involves a progression of telegraphed “victories” as Scott overcomes various challenges. Some of these victories have the exact same non-weight of a high score in an arcade game:

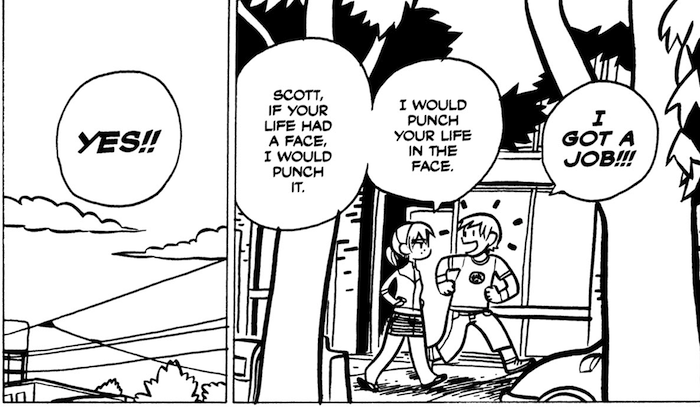

Others, on the other hand, track socially-defined life milestones, such as getting a job:

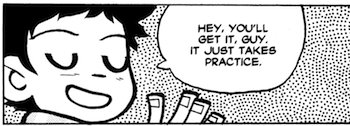

The real victories in Scott Pilgrim, though, like those in real life, are more subtle. For instance, a recurring piece of dialogue in the final volume is the phrase, “It just takes practice.” The first time we hear this, it’s Scott’s roommate Wallace responding to Scott’s complaint that he’s not good at “the sleeping around stuff”. Wallace’s advice to Scott, to go out and practice getting laid, is not very deep, although it’s probably more-or-less what Scott needs to hear at the time.

The real victories in Scott Pilgrim, though, like those in real life, are more subtle. For instance, a recurring piece of dialogue in the final volume is the phrase, “It just takes practice.” The first time we hear this, it’s Scott’s roommate Wallace responding to Scott’s complaint that he’s not good at “the sleeping around stuff”. Wallace’s advice to Scott, to go out and practice getting laid, is not very deep, although it’s probably more-or-less what Scott needs to hear at the time.

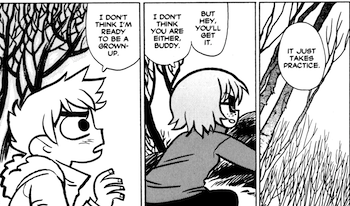

The second time the phrase is repeated is in a somewhat more serious, though still humorous, context; Kim and Scott are regrouping in the Canadian wilderness from their respective challenges, and Scott’s complaining of his unreadiness to deal with the pressures of adult life. Kim agrees with Scott’s self-assessment: he’s not ready. But she’s optimistic about his ability to learn, and in fact she consistently pushes him forward towards growing into the person he needs to be to make things work with Ramona and finish defeating the evil ex’s.

The second time the phrase is repeated is in a somewhat more serious, though still humorous, context; Kim and Scott are regrouping in the Canadian wilderness from their respective challenges, and Scott’s complaining of his unreadiness to deal with the pressures of adult life. Kim agrees with Scott’s self-assessment: he’s not ready. But she’s optimistic about his ability to learn, and in fact she consistently pushes him forward towards growing into the person he needs to be to make things work with Ramona and finish defeating the evil ex’s.

The final repetition puts the words in Scott’s mouth, near the very end of the volume, as he internalizes the lessons he’s been learning. Ramona is explaning to him her own challenges growing up and being able to commit to a relationship.

The final repetition puts the words in Scott’s mouth, near the very end of the volume, as he internalizes the lessons he’s been learning. Ramona is explaning to him her own challenges growing up and being able to commit to a relationship.

Scott: “We’d have to be careful… it could be a bumpy ride. It could get messy. But maybe… maybe it’d be worth it. Maybe we just need to hold on.”

Ramona: “I’ve never been good at holding on.”

And that’s the real moral stance that Scott Pilgrim takes. Life is about doing your best, caring for the people around you, and trying to hold on even though the world itself is amorphous and constantly changing. Or as David Foster Wallace put it in his Kenyon College Commencement speech, “The really important kind of freedom involves attention, and awareness, and discipline, and effort, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them, over and over, in myriad petty little unsexy ways, every day.”

So although Scott has seven “wins” over the course of the series, as well as a number of other telegraphed accomplishments, his real victory is his ability to keep moving forward, to keep living his life and accepting the confusion and messiness of the whole thing. As he says to Ramona, at the end:

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s characters in The Great Gatsby wrestled with how to move forward and create lives for themselves in the midst of a culture devoid of values. Although the ending of the book can be read as the narrator Nick Carraway learning and moving on, overall the ending has a pessimistic cast: Tom Buchanan and his wife Daisy’s lives are left in shambles, and the protagonist, Jay Gatsby, ends up dead in a swimming pool.

In real life, however, things weren’t so bleak. Although materialism in the 20s was followed by economic depression in 30s, plenty of people still went on to live fulfilling lives, and — agree or disagree with the assessment — the following generation was so much recovered from the lost generation’s malaise that it considered itself “the greatest.”

I wouldn’t stretch the parallels between Fitzgerald’s time and ours too far, but there are similarities: a discrediting of traditional sources of authority and values, rampant materialism and greed, as well as economic inequality and pessimism (we’re just getting it all bunched up at once instead of having it come in stages!) The question then becomes, what narratives do we construct about our lives against this backdrop?

What I like about the Scott Pilgrim books (beyond the non-trivial entertainment value) is that they tell an intelligently optimistic story. If the world doesn’t give us structure we believe in, we can invent our own make-believe structure for ourselves… as long as we remember not to take it too seriously. The message of the books is that people are fundamentally resilient, and that even in a crazy, relativistic world, values like empathy and growth still have meaning.

So…?

So… we try again.

- More Scott Pilgrim? What’s Scott Pilgrim? www.scottpilgrim.com

- I owe my high-school English teacher for my interpretation of The Great Gatsby… thanks Mr. Healy!