Consumer Culture, Creator Culture

On June 23, 2008, Pixar released WALL-E, a science fiction movie which predicted that humankind’s ultimate fate would be morbid obesity. In the movie, we retreat into space in technological wombs, leaving behind on Earth a planet-wide landfill, residue of our consumer culture, until we are rescued by a sentient robot that somehow restores our will-to-work.

On June 23, 2008, Pixar released WALL-E, a science fiction movie which predicted that humankind’s ultimate fate would be morbid obesity. In the movie, we retreat into space in technological wombs, leaving behind on Earth a planet-wide landfill, residue of our consumer culture, until we are rescued by a sentient robot that somehow restores our will-to-work.

WALL-E‘s premise was a reasonable attempt to forward-project cultural trends. Throughout most of the 20th century, America lived in a world of cheap calories and mass-produced content: a TV next to an Iowa cornfield. We stuffed our faces with food and our minds with reality shows, and it’s not too crazy a leap to extrapolate from that to couch-potato apocalypse. But today, that vision of the end seems as archaic as World World II propaganda showing Hitler marching through downtown Chicago.

There are two representative events that make me think that the world might end in fire, or it might end in ice, but it won’t end in lard. One was in September of 2006: Facebook released News Feed and Liking, and in literally under 24 hours, a hundred thousand people joined a group to protest; ironically, the rapid mobilization was made possible by the same-said technology, which, slightly modified, is increasingly becoming the basis for a new, participatory internet. The other was in September of 2008: only three months after WALL-E was released, Lehman Brothers collapsed, shattering the illusion that America was on a sustainable economic path. There will never be floating spaceships of the obese, because any civilization that would build them will be too deep in debt to afford it.

There are two representative events that make me think that the world might end in fire, or it might end in ice, but it won’t end in lard. One was in September of 2006: Facebook released News Feed and Liking, and in literally under 24 hours, a hundred thousand people joined a group to protest; ironically, the rapid mobilization was made possible by the same-said technology, which, slightly modified, is increasingly becoming the basis for a new, participatory internet. The other was in September of 2008: only three months after WALL-E was released, Lehman Brothers collapsed, shattering the illusion that America was on a sustainable economic path. There will never be floating spaceships of the obese, because any civilization that would build them will be too deep in debt to afford it.

Although the Lehman collapse, subprime crisis, and ensuing recession were shocks to the system, they are going to look like minor tremors compared to the convulsions coming in the next thirty years. In the Arab world, the revolution has already started, and so far it has been political. I don’t know what it will look like in America but I hope — considering the alternatives — that it will be economic.

Simply put, in a world where the population keeps on expanding, a culture that focuses on consuming is not sustainable. Thomas Malthus infamously predicted that the pressure of population against resources would lead to poverty and death. We now know what actually happens is that humans invent new means for creating wealth. In the past, that creation was largely focused on material goods, and although each burst of wealth disrupted the power structure in society — for instance, the rise of the Rockefellers on a wave of oil — things quickly settled back into equilibrium. Now, the medium of creation is information, the creators are everywhere, and there are too many of them for the cultural elite to assimilate them all.

We are surrounded by the walking dead. Blockbuster CEO Jim Keyes was quoted in 2008 saying “I’ve been frankly confused by this fascination that everybody has with Netflix.” Everyone laughs at that now after Netflix drove his company into bankruptcy, but that was just a foretaste of the economic disruptions ahead. Across every industry, the barriers to entry are dropping: making and distributing movies (cellphones + YouTube), building software (python/ruby + amazon web services), journalism (wordpress + twitter)… Even in “hard” industries like manufacturing, you can start to see the beginnings of the end. As the barriers to entry go down, the creators start kicking out the landlords. It becomes harder and harder to sit on your ass and collect rent; to survive, you have to create value for other people.

Success in a creation economy requires a different set of characteristics than success in a consumer economy. Authenticity becomes more important than presentation. Speed becomes more important than size. Personal responsibility becomes more important than office politics. Pointy-haired boss better hope he has a good retirement plan. There is going to be, there already is, a fundamental shift in power into the hands of the people who master the tools of the new mediums. The revolution will not be televised, but it will probably happen on Apple hardware. And the people who create are not going to be satisfied seeing the results of their labor fed back into the black hole of the federal healthcare budget.

Success in a creation economy requires a different set of characteristics than success in a consumer economy. Authenticity becomes more important than presentation. Speed becomes more important than size. Personal responsibility becomes more important than office politics. Pointy-haired boss better hope he has a good retirement plan. There is going to be, there already is, a fundamental shift in power into the hands of the people who master the tools of the new mediums. The revolution will not be televised, but it will probably happen on Apple hardware. And the people who create are not going to be satisfied seeing the results of their labor fed back into the black hole of the federal healthcare budget.

Every generation is a historical anomoly. The great anomoly of the 20th century was the utter lack of demands placed on the citizens of first-world countries. To pick an extreme example at the other end of the spectrum, the citizens of Sparta in ancient Greece were expected to maintain superb physical health and athletic fitness, devote their lives to training for combat, and endure a life of austerity and hardship; in exchange, their civilization became one of the great powers of the ancient world. The rigors that will be required for economic survival in the next few decades will be different — less obedience and conformity, more creativity and vision — but the fact is, the bar is going to be raised and not everyone will make the cut.

Every generation is a historical anomoly. The great anomoly of the 20th century was the utter lack of demands placed on the citizens of first-world countries. To pick an extreme example at the other end of the spectrum, the citizens of Sparta in ancient Greece were expected to maintain superb physical health and athletic fitness, devote their lives to training for combat, and endure a life of austerity and hardship; in exchange, their civilization became one of the great powers of the ancient world. The rigors that will be required for economic survival in the next few decades will be different — less obedience and conformity, more creativity and vision — but the fact is, the bar is going to be raised and not everyone will make the cut.

Losing weight isn’t easy. We have an education system, a political system, an agricultural system, and of course an economic system that have all been optimized to satisfy the basic material comforts of as many voters as possible, as well as the extended material comforts of a somewhat smaller subset. In other words, we are trained and groomed from birth to be fat, lazy and dumb. This is the world we built for ourselves; this is the fruit of our ancestor’s success. We got here with good intentions, but it’s a local maximum, not a global maximum, and therefore it’s a trap. Escaping from a local maximum is hard to do on your own. The more people who make it out, the easier it will be for us as a whole to ride the transition from a consumer culture to a creator culture succesfully.

I like the announcement they make on airplanes: put on your own oxygen mask first, then help the people around you. I don’t think we’ll crash, but we may experience sudden shifts in cabin pressure. So, if you don’t know where the oxygen masks are, the time to start looking around is now…

I like the announcement they make on airplanes: put on your own oxygen mask first, then help the people around you. I don’t think we’ll crash, but we may experience sudden shifts in cabin pressure. So, if you don’t know where the oxygen masks are, the time to start looking around is now…

Keep Moving Forward

So I was thinking about how it’d be fun to give one of those inspirational, I did it, you can do it too speeches. And before I knew it, I actually wrote one in my head. Unfortunately, no one’s going to invite me up on a stage to talk about how I HAVEN’T built a succesful business and written a revolutionary tract on moral philosophy. And by the time I have, I’ll probably want to give a different speech. So I’m going to be lame and share this one now, even though I have to put my accomplishments in placeholder brackets, and of course it’s all probably bullshit since I’m just making it up. Whatever, I’m a dork, and this is my blog.

Brace yourself, here goes:

Dear blah blah blah, great to be here, blah. Insert dumb comment about the venue. Today we’re going to talk about entrepreneurship, and the “founder’s psychology”. A lot of people will tell you that it takes a certain type of person to be an entrepreneur. You have to have a high risk tolerance. You have to be a rebel or a rule-breaker. You have to be nerdy like Mark Zuckerburg. You have to really want it. I dunno, there’s a bunch of theories. I’m here to tell you that that’s all bullshit. 100%, absolute, total crap. The next time someone starts talking to you about the personality type it takes to be a founder, what I want you to do is stick your fingers in your ears and start singing “nah nah, nah nah nah nah, hey hey, good bye”. And then walk away.

The actual truth of the matter is that success, in any venture, enterprise, endeavor, quest, or vision, has nothing to do with personality. Or, more accurately, “personality” is just a way of describing the sum total of a person’s attitudes and behaviors. Some of those behaviors you can’t change, like the fact that you lisp like your Uncle Henry, and others you can, like the fact you punch Uncle Henry every time you see him. And the ones relevant to success are the latter.

What success actually comes down to is learning principles. We live in a universe governed by natural laws, which dictate principles for achieving things. If you want to build an airplane, all you need to do is master the principles of thrust, lift, drag, and weight: if you got those right, it’ll fly; if not, it won’t. No one is born understanding thrust… we had to figure it out, and once we did, airplanes turned from something that people thought was impossible to something people churn out in factories multiple times a day.

The really good news is that people are principle-learning machines. We were built for this. Picking up principles is as easy as learning to walk. In fact, that’s what learning to walk was. Take out a piece of paper — don’t actually do this, I’m talking right now — and write down everything you know how to do, from tying your shoes to driving a car to picking up attractive people in bars. Every one of those represents a victory of your natural mechanism for learning principles. Most of these accomplishments you probably take for granted now. But the very same thing that made those possible, is what enabled us to build the Manhattan skyline, for F. Scott Fitzgerald to write the Great Gatsby, for {insert president’s name here} to convince half the country he’s better than the other guy.

Wait, you ask. If it’s so easy, if it’s just human nature, why am I not president of the united states? (I’m sure you think you’d do a better job, right? Come on, admit it). I have that idea for a company. Or a book, or a sculpture, or an inner city agency to help teach kids how to play classical guitar. But it hasn’t happened yet.

Well it turns out there’s one meta-principle. A principle that makes the difference between whether or not you succesfully acquire all the other principles that you need. One principle to rule them all, you might say.

I think every succesful person would articulate it differently, but I think they’d all recognize it. You recognize it, because in your own way, you’re succesful too — you’ve done stuff, accomplished things… whether or not you’re happy with what you’ve accomplished, whether or not you’ve accomplished up to your full potential, the fact of the matter is you probably wouldn’t be sitting here if you were completely oblivious. Think back on all the moments in your life where you did something, grew as a person, moved forward, become more of an adult and closer to the person you want to be. What’s the common thread that you see?

I see a common thread, and the way I would articulate it is, “keep moving forward.” That’s the master principle. To be succesful in life, what you must do, is you must keep moving forward. Another way of putting it, is “let the universe tell you ‘no’.” It’s your job to decide what you want. And then it’s your job to keep moving forward. And it’s the universe’s job to try to stop you. Do you want to revolutionize the fashion industry? Do you want that cutie to be your significant other? Do you want to be suntanning on the beaches of Argentina? Do you want to write a book that’s read a thousand years after you die? Decide what you want, keep moving forward.

As long as you keep it straight — your job, move forward; universe’s job, say no — everything works great. It’s when you get confused and let the universe move things forward while you tell yourself ‘no’ that things go to shit. There are a million little ways we tell ourselves no every day. “I don’t think I deserve to have a great job, I’m not good enough.” “I don’t think she likes me.” “I can’t introduce myself to him, he’s famous!” “Maybe that book isn’t such a good idea after all.” That’s how failure happens. Because you can’t do two jobs at once. If you’re doing the job of telling yourself no, then you’re not doing your job of moving forward. And if you don’t move forward, guess what: you won’t go anywhere. Duh, right?

It’s actually relaxing to let the universe take over the work of telling you no for you. Maybe you’re actually not good enough for him: great, he’ll walk away when you try to talk to him. Maybe your vision for a company is impossible: great, investors won’t give you any cash. The universe does its job very, very well. It can and will come up with more creative ways of shutting you down than a hypochondriac worry-wort’s wildest dreams. Honestly, if you try to beat the universe at its own game, you’re out of your league. It’s far better just to play dumb and keep on operating as though you will start the company and get the lover and write the book and just keep on going until you run smack into a brick wall. Because sometimes, you will, but other times, the brick wall won’t actually be there. Just keep on moving forward and find out.

There’s a million ways you can keep going. If your business partner gets sick and can’t work any more, then you can find a new one, proceed without a partner, or see if you can work with her around her illness… or any other solution. No matter what disaster happens, as long as you’re not telling yourself ‘no’, it’s actually very easy to brainstorm ways of taking the next step.

So let’s go back to the founder psychology for a minute. The interesting thing is that some people seem to — from whatever childhood experience or genetic disease or whatever — seem to be born really getting it, and others life has to basically hit them over the head with a two-by-four before they catch on.

I’m in the latter category, by the way. I didn’t have a clue for the longest time. I would think myself silly trying to figure out, why isn’t my life going the way I want it to, and make it super-complicated, and blah blah blah blah blah. I mean, I was really terrible. I couldn’t tie my own shoelaces. I was the guy in class who’d try to make the insightful comment in the hope that people would hear and go, wow, you’re really insightful, let me make you famous now. Yeah, I was that guy, sorry everyone. I didn’t get the girls, I didn’t make an impact, I didn’t achieve my dreams. Because I was trying to have the universe do my job. I was hoping that if I stood there and smiled and waved, it would move things forward. Things only started turning around for me when I realized that that it was on me to make things happen.

Anyway the reason I’m telling you this is that I want to make the point that, whether or not the “keep moving forward” thing is something that comes to you naturally or not, you can learn to think that way. You don’t need the “high risk tolerance” gene. You don’t need to have been raised by bears in the forests of Africa, learning how to rip out the hearts of deer with your bare hands. You just gotta keep reminding yourself, “am I saying no or am I moving forward? Am I doing the universe’s job or am I doing my job?”

Okay, some typical objections. Number one: but it’s scary!

Actually, if you get so far as to realize how unbelievably scary it is, you’ve made a lot of progress. Most people are so busy rationalizing to themselves why they don’t move forward that they don’t even recognize how terrifying actually going after your dreams is.

Anyway the fear thing is really easy. Have you ever jumped off a high cliff into a lake? You can stand on the edge of the cliff for twenty minutes going back and forth, talking yourself into it, talking yourself out of it, shivering and looking really dumb in your bathing suit, etc. etc. But then the second you’re like, “oh well, what the hell” and jump, boom, you’ve just done it. The antidote to fear is acting. And you don’t need to “beat” or “master” or “conquer” your fear first, you just have to act. And most action is over so quickly, there’s almost not even time to fuck it up. For instance, “hi boss, I’d like to quit my job because I want to start my own business”…. oh shit oh shit oh shit what did I just say did I just say that oh well, too late, security’s showing me out the door, guess I better be an entrepreneur now….

It’s okay to scream like a 5-year-old girl going down. It’s all good. You’re allowed. Tarzan bellowing might be classier, but either way you hit the water, and that’s what counts. Just keep moving forward.

Number two objection: but I don’t know which way forward is! What do I want?? Yeah, this one really nailed me for a while. Should I write a book? Start companies? Join the peace corp in Africa? I don’t know!!!! How do I decide!!! Watching a freshman trying to choose their college major is often like this. You want to put the poor creature out of it’s misery, it’s just awful to watch. The trick is… being right is not important. It is far, far better to make a bad decision and act on that decision and experience the consequences of that decision then it is to not decide. Most people interpret Nietzsche’s “That which does not kill us makes us stronger” as creepy Teutonic bravado, but I actually think it’s just really down-to-earth good advice.

Fact: the only way you learn what you want, and how to get what you want, is to try things and see what happens. You want to be an astronaut and also be a doctor? Flip a coin then spend a summer interning with one of them. Still can’t decide? Spend the next summer interning with the other. Still can’t decide? Flip another coin, then major in biology. Still can’t decide? Flip a coin, then go to med school. Still can’t decide? Open a private practice. Just keep moving forward until either a) you have more clarity or b) you wake up one morning and realize that you’ve achieved one of your dreams. And you know what? Worse come to worse, you can do both. Maybe even simultaneously if you’re really Mr. I-can’t-make-up-my-mind. It’ll be harder, but then, “hard” is one of those things that it’s the universe’s job to worry about. Most indecisiveness is really disguised procrastination. Don’t do it. Yes, you may find yourself saying, in the words of Michael Bluth, “I’ve made a huge mistake.” But hey, that’s half the fun of life. Just keep moving forward.

Update

I don’t want to write a journal here, but I alo can’t completely divorce my opinions from who I am. Most of what people say and think is bullshit derived from the imperative to protect their identity, and I’m no different. Context on what that identity is lets you see a thought for what it’s worth, or isn’t, as the case may be. So here’s an update on what I’m up to.

My short term goal is to launch KeywordSmart with my partner Jody: it’s a software product for people who need to keyword (ie, tag) images in order to make them searchable. The target demographic for this is, for the most part, professional photographers who sell their images on stock photo sites. We want to launch this product and build it into a company, and see where it goes: we know there’s a pain point that needs solving, and we have something in mind to solve it, and at the end of the day, that’s what a business is, so we’re going to try it and see what happens.

Longer term, what I want to do is write, specifically a book on philosophy and values. My thesis is that people are humans — special, worthy of praise, etc. whatever — insofar as they see themselves as responsible for who they are and how they react to the world around them. I believe that this thought — “I am responsible” — is a self-fulfilling prophecy: insofar as you don’t believe it, your actions are explainable in terms of external forces such as your heredity and environment; insofar as you do believe it, you become capable of increasingly spontaneous action, transcendent behavior that seems to defy explanation outside of spiritual vocabulary. Seeing oneself as free, responsible, the author of one’s own actions is a constant battle, and victory in that battle underlies all great human accomplishments, while failure leads to entropy, regret and oblivion.

Why philosophy? Isn’t it just asking over-intellectualized questions with no real fruitfulness? Who cares about abstract notions when there are things to experience, people to love, things to create and build? Honestly, part of the reason I want to write this book is so I can stop thinking about it and do just that. There’s a cliche about living life like each day is your last, and the cliche probably comes from the real experience that people who’ve faced death can see what really matters to them. To me, philosophy is about the death of the self — not physical death, exactly, but the death of constructed identity, the stories we tell ourselves about who we are and why we exist and what we’re doing. The great paradox is that these stories are both pernicious and necessary. They are pernicious because they get in the way of taking life as it is: they impose false constraints and illusory future visions that stop us from seeing what is right in front of our eyes. They’re necessary, though, because a sense of self is what allows us to take action — without a sense of who we are, we become paralyzed lumps, fleeing fear and seeking empty pleasure. The solution to the paradox is to ask “why” and keep asking until everything false about the self dies, and we’re left with who we really are.

Maybe you can get to that same place without asking the questions. I think it may be too late for that, though: as a culture, we’ve gone past the point of no return in terms of opening the doors to questioning. We’ve already asked “why” to all the traditional sources of identity such as culture, religion, and ideology. Once you open the door to wondering, I think it may be a one-way road: either you make it to the bottom of the rabbit hole, or you get permanently lost along the way. At any rate, I’m the kind of person who experiences the world in abstract terms, so whether or not there are other solutions available to other people, I need to go all the way and see what lies at the end of the path.

So that’s me right now. I’m working on a technology startup to help professional photographers sell their images online, and I’m trying to reinvent philosophy to provide a coherent narrative about what it means to be a person in a world where we can doubt everything. I honestly don’t know if these goals make any sense at all, but all my regrets I have at this point in my life are on the side of failing to act: not doing anything and being swept along by the pain / pleasure impulses, avoiding hard things and looking to food and entertainment for distractions. I’m near the end of my own patience for myself, and the funny thing is that self-respect doesn’t seem to require sanity, it just seems to require action. So: I’m going to write code, and I’m going to write philosophy, and I’ll see what happens.

Faith for Atheists

This is probably a little more timely than I really intend it be, this being the rapture and all, but I want to talk about faith. We have a culture where faith is associated with religion; it’s a two-for-one sale. Atheists don’t have faith. Theists do. And then there’s the murky middle, the “spiritual but not religious” masses who don’t really buy the whole religion thing but want to keep one foot in the door of higher meaning.

This post is for the people in the room who want to buy only half of the package deal.

People are delicate, pathetic things. A strong wind, an errant car, or even a rogue microorganisms can wipe us out like a foot crushing an ant, and those lucky enough to survive external threats to their existence eventually fall apart from the inside out. We all stand next to complete disolution, and for the most part just try to distract ourselves until we get so senile that we die without worrying about it too much.

From time to time, events force us to confront the fact we live in a world outside our control, that we are small and it is big. Sometimes a new episode of Jersey Shore isn’t enough to distract us. At those times, when we confront this face on, the two reactions are horror or awe: raw, nihilistic despair that we live in a meaningless world where absolutely everything we care about and work towards will die, or a heightened sense of aliveness and appreciation of the preciousness of each ounce of our limited span.

Let’s call the quality that allows awe and dispels horror “faith.” It is the feeling that the universe will meet us halfway; that though our existence is pathetic, we have our small part to play and if we play it well there is joy for us in it. Or in other words, that we live in a universe that we can look at and say, “this is good”, even as we watch kids die in car accidents and genocide in Africa and our smarmy coworkers get promoted ahead of us.

I think true faith is something experienced, not believed. We all have lots of beliefs, most of which are bullshit. A belief is just a theory that we haven’t gotten around to disproving yet. Staking our hope on a belief always leads to cognitive dissonance, because the human mind seeks truth and always knows at a deep level when we’re clinging to something that we hope is true but have no evidence for. Experience, on the other hand, is direct perception; you don’t believe that you’re feeling happy, you know it, because that’s what happy is.

Religion can breed true faith by calling attention to the abyss and providing community support in facing it courageously. But it also breeds a lot of false faith, by propagating hearsay claims: we live in a good universe because there is a God out there who will reward or punish us. These consquences are hearsay because, in most versions of the story, you have to be dead first before you get to experience the fun firsthand. Hearsay creates belief, but it can’t create experience. I think a lot of religious fanaticism is underlied by a deep insecurity, a subconscious acknowledgement of the foundational weakness of the position, where the response is to attack anyone who dares question our hopeful narrative. (I say “our” because everyone does this from time to time — we all have beliefs that we are fundamentalists about).

So I don’t think religious faith — the good kind — can be related to God as the provisioner of moral consequences. Rather, I think where belief in God and faith can overlap is when God is used as a metaphor for our perception of the universe. The faithful sees the universe as personal: love, not emptiness, underlies the cosmos; the abyss is illusionary and life has meaning.

But one metaphor can be discarded for another. You don’t have to believe any external fact about the world to experience the universe as fundamentally good. In fact, I would argue that dropping the talk of God can even make our perceptions of this clearer.

Unfortunately, the predominate discourse in our society is that science — generally viewed as the other option for understanding our reality — tells us that we live in an amoral universe. We’re just collections of elementary particles or vibrations of very tiny strings, evolved by natural processes into beings that, for various survival-driven reasons, display moral sentiments as the occasion warrants.

That’s almost right: science is in fact amoral. But science is amoral because the scientific method works on the world viewed from a third person, objective perspective; value judgments occur from a first person perspective. Science says nothing about the moral content of our existence; it doesn’t speak the language. I think a lot of people would say that it really comes down to us whether or not we see the universe as fundamentally good or bad, empty or meaningful. My personal opinion (which I’ll try to write about later) is that the nature of human consciousness itself makes life meaningful. Either way, though, the point is that experiencing the universe as fundamentally good is something that you can do regardless of what you believe re: metaphysics, Gods, spaghetti monsters, etc. So I’d like to reclaim faith as something that everyone can do, not just the (officially) faithful.

Editing vs Writing

Imagine that you’re in a martial arts showdown against a practioner of some obscure Eastern training. Your opponent has been preparing all his life for this moment, honing his body and mind into animal-like grace. You’re just an average office-rat; maybe you go to the gym a few times a week. You are now in a jungle pagoda battling for your life.

Now, imagine time slows down. It takes a subjective minute for each of your punches to connect… it’s like the air became molasses. You have as much time as you need to study your opponent’s body position, feel the balance of your weight, correct your motion, and prepare your mind for impact. Suddenly, you’re not panicking anymore; the fear and adrenaline are out of the picture and you weigh your options like a chess player.

Let’s assume your opponent feels time normally. Let’s also give you the benefit of the doubt re: your athleticism; you can move, you can hit harder than a five year old. Now it’s your opponent who is in trouble. With an infinity to study each step, you react as though possessed with uncanny intuition. It’s Mr. Smith fighting Neo in the Matrix; Mr. Smith is screwed.

Writing is about inspiration; editing is about technique. The former seems mysterious and passionate whereas the latter is coldly analytical. An editor sees a text as a series of decisions, and the most skilled editor is the one who can articulate most precisely the pros and cons of each, whether that’s the placement of a comma, the grammar of a sentence, the choice of a word or a particular metaphor, or the omission or inclusion of a passage. There’s no magic to it; just refinement, adjustment, and frequent reference to Strunk and White.

There are many great editors who are not great writers. You cannot write the great American novel by writing a shitty American novel and then revising it until it is perfect. You can’t do that because perfect is optimization within constraints, whereas great is breaking through constraints to create new landmass out of thin air. Two entirely different goals, dictating entirely different exertions.

Nevertheless, different as they are, the two practices are intimately connected. You can imagine great writing as a great editor fighting the kung fu master in slow motion. With a subjective infinity to make each editorial decision, the objective appearance is a fluid stream of creation, giving the impression of mystery and magic. From the view of the time-slowed individual, though, it’s just a series of choices — which metaphor, what sequencing, which word — the same choices that editors critique and revisit after the fact.

If writing and editing involve the same decisions, that raises a puzzle. In a real fight you can’t slow time, but in writing, it does seem as if time is in fact frozen: at least, your word processor isn’t about to pick itself up and run. So why can’t you substitute editorial prowess and a lot of patience for great writing’s elusive special stuff?

The missing piece of the analogy is the opponent. You’re back in your jungle pagoda; time is frozen; but this time, you’re by yourself. Now an observer walking by doesn’t see a martial arts expert — if you try to do fancy kung fu footwork, you’ll just look stupid. It was your opponent who forced your reaction; raw necessity of survival drew the lines of efficiency that lent your movements grace. Absent something to react to, the lines aren’t there.

Call the thing that writers react to inspiration: a psychological or maybe spiritual necessity to express. Inspiration waxes and wanes, and as it flows one must react by choosing a vessel to fill with it. Nothing a human being can write in human language will ever fully do justice to the original urge. But you can do better or worse. Drops of intuition will always escape and spatter on the ground, but you can hold up a sieve, or you can hold up a cup, or you can hold up a jug. Time does not freeze for writers — you must make decisions, big decisions, about what form to choose, and after the fact you can correct certain choices but only up to a point — beyond that point you need a fresh stream of inspiration or else you will kill what you’re working on.

So like a real martial artist, a writer needs to learn to practice making decisions under pressure until good choices become intuitive rather than conscious. Editing ability helps with that, because the better you can critique your work, the less error your practice will introduce into your technique. It’s doing katas in front of a clear mirror instead of a cloudy one. But recognition of good is still completely seperate from ability to do.

The joy in this thought is that practicing is never-ending. It is a great thing to feel the surge of inspiration, frantically pour it onto paper, and even as you write, feel the inadequacy of your technique to do your impulse justice. That’s because you can never, no matter how good you are, capture all of an inspiration. Creative choices are discrete, whereas inspiration is continuous. Inadequacy and imperfection are in the very nature of life itself, and life’s blessing is that, being imperfect, there is always joy in getting better. My technique is a clumsy vessel — I feel how weak it is, how insubstantial my imagery, how heavy-handed my weaving of point and story, and that’s fine, the natural order of things. Water will always splash from my cup, and the splashing is good. And sometimes the cupping is pretty good too.

Oh, I could build a tool to do that

So after I wrote about what I would teach if I was substitute teacher for a day, I realized that it doesn’t have to be hypothetical. I build web applications, and this is a pretty good candidate for a simple web application to walk people through the process.

Here’s what I’m thinking: you sign up with an account, and submit things that suck, both for you personally (my apartment is too small), and broader issues that you care about (the park next door is all littered). You can keep them private, or share them anonymously or publicly. You can then enter suggested action steps for your own problems or for other people’s. The site tracks over time what happens with each of the problems, and gives you feedback and points or whatever for solving them.

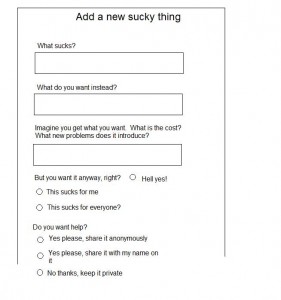

This is a mockup of how I’m visualizing the submission form (I just registered the domain nomoresuck.com):

(Warning: building mockups in MS Paint is extremely hazardous and should only be attempted by trained web professionals).

Thoughts? Advice? Would you use this?

Substitute teacher for a day

In my last post, I asked the question, what would you do if you got to be a substitute teacher in a middle or high school for a few days, and got to teach whatever you wanted? What’s the most important, most impactful thing that would make a difference in the lives of your students?

I guess it’s only fair that I take a stab at answering it. (I still want to hear other people’s answers… if I hear any good ones I’ll post them in a follow up). It’s a little scary to imagine myself responsible for making a difference in the lives of a roomful of kids, but here goes…

For me, I think the number one most important lesson is the power of taking responsibility for your own life. There’s two parts to this lesson: 1. nothing is going to change unless you say “I am going to make it change”. 2. You’re not on your own — once you take responsibility for making something change, it’s fair game to bring in others to help.

Those two beliefs are basically acts of faith. You can go through life not believing them, and maybe things will turn out okay, but you’ll be at best a passive spectator in your own life. When I think about the kind of person I want to be, and the kind of person I want to share the world with, this is where it all starts.

Standing up in a classroom and talking about this idea is worthless, though. This is the kind of thing that has to be shown, not told. I don’t know if this would work, but what I would try is walking the class through the steps one by one for things in their own lives:

1. Identify that there are things I want changed. This can be really hard, because it’s easy to get used to problems and become blind to them. The strategy to deal with that is to put aside the thought of solving the problems until I’m done identifiying them — keep it purely hypothetical.

Lesson plan: Have the students take out a piece of paper, and write a list of problems that they are having with their lives. This could be anything from getting bad grades in math class, to not being as popular as they would like to be, to being worried because their mom was diagnosed with cancer, to hating their hour-long bus commute to school, or anything else.

2. Figure out what I want. It can be hard to be honest with myself about what I really want in a situation! Also, I need to balance realism with ambition: I need to set my aspirations high, but not so high that it really does become impossible.

Lesson plan: Have each student write down, next to each problem, two things. First, what they would do if they had a magic wand to fix the problem. Become a math genius. Become the most popular kid in school. Have their mom recover. Switch to a different school. Second, one thing that would make the situation substantially better even if they couldn’t make it go away. Get good grades in a different class. Make a few new friends. Make their mom feel better and less afraid. Find something fun to do on the bus ride each day.

3. Commit to taking responsibility to make the change. This is the hard, critically important step. The thing to note here is that there is always a cost to getting what I want (‘be careful what you wish for’) and if I am not willing to pay the cost, I am not going to succeed in making the change.

Lesson plan: Have the students imagine that they have just waved their magic wand. Write down anything scary or unpleasant about the new situation. Will other kids think they’re I’m a nerd if I get good grades in math class? If I’m the most popular kid in school, will I be under a lot of pressure to keep that popularity up? Then have them ask themselves, is it worth it? If the answer is no, cross the problem off their list. If yes…

4. Generate ideas. The question here is “What is one small action I could take today that would move me closer to improving the situation?” Or, “If James Bond / Superman / Sherlock Holmes / Barack Obama / The Man with the Iron Mask was in my shoes, what one action would they take today?”

5. Ask for help. It’s often much easier to see the solutions for someone else’s problem than it is for my own.

Lesson plan: Have students write down one of their problems along with what they want on an index card. Label it with a code that is anonymous to everyone else but that they’ll remember. Redistribute cards, brainstorm solutions for the problems on the card that you get, then mix the cards up again and have people retrieve their cards.

6. Execute! The homework assignment is to do as many small actions as you can. The class discussion the next day is, were you able to? What went well and what went badly? What did we learn? Then the homework for the following day is, try again….

Education: Not better, different

One of my biggest personal pet peeves is that the American education system is basically useless in terms of preparing students for life.

One of the cliches about the value of a liberal arts college education is that it’s supposed to teach you to “learn how to think”, as opposed to the rote memorization of knowledge. Okay, so my first problem with that: what is the twelve years of education leading up to college supposed to teach? How to hold your pen? And then my second problem is that once you actually get to college, you’re taught how to think a little bit, but as measured by volume, that’s only a tiny fraction of the contents.

There are various cynical theories about how public schools are basically glorified daycare centers to keep children out of the way of adults. Whether or not that’s true, the net result is that the primary things schools teach are: a) a level of basic literacy in language, mathematics, science, and culture that’s woefully un-competitive with the rest of the world, b) how to anticipate what authority figures want, and c) how to sit still, shut up, and raise your hand when you have something to say.

Seth Godin recently wrote a really great blog post that sums up a major trend: the era where you could guarantee yourself a comfortable economic future by coloring within the lines is basically over. The rise of the internet is wiping out a lot of career paths, and the new opportunities that are opening up are ones that require creativity and entrepreneurialism, attributes that are completely un-correlated with getting a 2400 on your SATs. (This is probably related to why a lot of top graduates from Ivy League schools take jobs in finance: investment banking is one of the rare lucrative pockets of the economy where this trend hasn’t taken over yet).

Speaking personally, the thing that’s gotten me the most job opportunities — my ability to develop software — is something that I learned almost entirely outside the classroom. I did learn valuable things in school (how to write, for instance), but on an hour-for-hour basis, when I look at the time I spent in class and doing assignments, and when I look at the lessons I’ve learned that I consider important, the whole thing has been criminally wasteful.

There’s a lot of innovation going on in the education space — the charter school movement, for instance — but I’m worried that most of it is oriented at doing a better job against our current goals: getting more kids into better colleges with higher test scores. What I really think we should be doing is changing the yardstick. What we need are graduates who know how to think for themselves, set and achieve goals, and engage with the changing world flexibly and creatively. Happy, healthy, and sane would be good too. Right now those are all peripheral to what education focuses on, which is tragic.

I have a question for everyone: if you got to be a substitute teacher in a middle or high school for a few days, and got to teach whatever you wanted, what would you teach? What one lesson is the most important thing you could convey? I’ll share what I would do over the next few days…

And his name shall be “Awesome”

Good writing is writing that conforms to Strunk & White’s dictum, “omit needless words; omit needless words; omit needless words”. Good writing is humble; authors say no more, no less than what it takes to make their point. This takes an element of courage, because authors must be willing to strip their message bare and expose it naked to the world.

Great writing is writing so humble that it folds back around and becomes arrogant. Great writing is fearless. My favorite writers project an almost obscene confidence, as if they are saying “yes, I understand that others use the English language that way, and now I choose to use it this way instead.” They use extra, needless words, and they use them because they damn well want to use them, and of course they could make it shorter but that wouldn’t be as fun.

Here are three examples:

Steven Pressfield argues in The War of Art that failing to act on one’s passions is the root of all suffering:

If tomorrow morning by some stroke of magic every dazed and benighted soul woke up with the power to take the first step toward pursuing his or her dreams, every shrink in the directory would be out of business. Prisons would stand empty. The alcohol and tobacco industries would collapse, along with the junk food, cosmetic surgery, and infotainment businesses, not to mention pharmaceutical companies, hospitals, and the medical profession from top to bottom. Domestic abuse would become extinct, as would addiction, obesity, migraine headaches, road rage, and dandruff.

Yes, that’s right, the cure for dandruff is pursuing your dreams. Man, think of all the money you could have saved on Head & Shoulders. And you know what? He says it with such conviction I sort of believe him.

A few lines from “Lean times in Lankhmar”, by Fritz Leiber, imho the best short story ever written:

…the gods in Lankhmar sometimes seem as if they must be as numberless as the grains of sand in the Great Eastern Desert. The vast majority of them began as men, or more strictly the memories of men, who led ascetic, vision-haunted lives and died painful, messy deaths. One gets the impression that since that since the beginning of time an unending horde of their priests and apostles (or even the gods themselves, it makes little difference) have been crippling across that same desert, the Sinking Land, and the Great Salt Marsh–to converge on Lankhmar’s low, heavy-arched Marsh Gate–meanwhile suffering by the way, various inevitable tortures, castrations, blindings, and stonings, impalements, crucifixions, quarterings and so forth at the hands of eastern brigands and Mingol unbelievers who, one is tempted to think, were created solely for the purpose of seeing to the running of that cruel gantlet.

The word “crippling”, cannot, in fact, be used to refer to a form of progressive movement — that usage does not exist in the English language. Did Fritz Leiber know that? Probably. Did he care? Nope. “Chutzpah” as a term was probably invented by someone who had just read a Fritz Leiber story. But Leiber gets away with it because he leaves you with images — hordes of impaled and crucified priests, crippling across an endless desert, for instance — that you will never forget.

Finally, some dialogue from Byan Lee O’Malley’s Scott Pilgrim and the Infinite Sadness, which is a graphic novel and thus not real writing at all:

The protagonist Scott is getting his ass kicked by his nemesis, Todd, who has psychic powers because of his vegan diet. Todd’s girlfriend Envy, who has just learned Todd cheated on her, is watching.

Scott: “I can’t even get near him! I need some kind of…like….last minute, poorly set-up deus ex machina!!!”

Immediately prior to this, Scott was almost — but not quite — rescued by an intervention that can only be described as a last minute, poorly set-up deus ex machina… so… wait a second…

Two men pop up out of nowhere.

“FREEZE!!”

“VEGAN POLICE!”

They are pointing their fingers at Todd as if they were holding imaginary guns.

Cop 1: “Todd Ingram, you’re under arrest for veganity violation!”

Todd: “What’d I do? What authority do you represent?! YOU CAN’T DO THIS! I DIDN’T DO ANYTHING! YOU CAN’T PROVE ANYTHING! I’M A ROCK STAR!”

Cop 2: “We have it on record that at 12:27 this afternoon you did knowingly consume a restricted food item.”

Cop 1: “Gelato, bitch.”

Todd: “What? It… it wasn’t me!”

Envy: “Hang on… Are you saying gelato isn’t vegan?”

Cop 1: “It contains milk & eggs, ma’am.”

Envy (thinking to herself: “it sounds delicious”)

Envy: “…is chicken parmesan vegan?”

Cop 2 (aside): “Is it?”

Cop 1: “I’m not sure. Isn’t ‘parmesan’ like a rodent or something?”

Envy (pounding on Todd): “YOU LIED TO ME!!!!”

There is so much WTF in this passage I can’t even begin to parse through it. And yet the logic — in regards to the salient plot details, and more subtly, Envy and Todd’s respective reactions in light of their characters — stands up flawlessly. Dadaist it may sound, but it’s constructed as carefully as any scene in a Eugene O’Neil or Arthur Miller play. And if you didn’t know what a parmesan was, wouldn’t you think it sounds like a type of rodent?

Nutrition, Psychology, and Reductionism

I have the most ridiculous 2 am thoughts. Â Like, why am I thinking about this right now? Â It’s totally random. Â Anyway, here goes:

So there’s an ongoing debate in the sciences about “reductionism”. Â If I’m a reductionist, I believe that psychology and nutrition are just applied biology, that biology is just applied chemistry, that chemistry is just applied physics (and is physics just applied math?) Â Note that you can remove the word “just” and make the reductionist position sound less condescending, depending on your taste. Â If I’m not a reductionist, I believe that there are facts / laws about psychology + nutrition that can’t be paraphrased / explained in terms of biology. Â These facts “supervene” on the underlying physical facts, or perhaps they “emerge” from a sufficiently complex system, whatever that means.

It’s an unsolved debate right now. Â On the reductionist side of things, you have chemistry, which (as I understand it — chemists please jump in) reduces to physics fairly nicely. Â For instance, the interactions of the periodic table can be explained in terms of the mixture of protons, electrons, and neutrons in an atom. Â As you get further and further out from chemistry, though, our ability to deductively reason about things gets weaker and weaker. Â I think (oh god I’m sure I’m getting this totally wrong) that RNA folding into proteins is currently partially reduced to chemistry: we can explain why any given protein structure is stable by reference to chemical bonds, but on the other hand, we can’t reliably calculate in the other direction and figure out what combination of RNA will fold into any given molecular shape (though we’re working on it).

If you zoom out to psychology and nutrition (which I’m picking on because a) they are generally labeled as being “science” vs something like sociology or economics where people feel obliged to qualify it as being a “social science”, and b) because I find them interesting), we really know stunningly little, and our ability to make meaningful predictions at the level of the whole human being is pretty much, despite all the research that has been done, garbage. Â That’s a strong statement, but let’s look at the state of the art.

In psychology, for a large part of the 20th century, the establishment took Freud’s theory that the mind could be subdivided into the id, the ego, and the superego seriously. Â In terms of scientific rigor, I’d put that as roughly comparable to Hippocrates’ theory that the human body consists of yellow bile, black bile, blood, and phlegm. Â Over the last 40 or 50 years, things have gotten a bit better, and we know now things such as: if I fry brain region X, you lose ability to do Y, and if I feed you drug Z, this will stimulate brain region Q. Â There’s also been a plausible effort done mapping out a lot of the more automatic circuity of the brain: we can tell a reasonable story, for instance, about how incoming light becomes representations of objects becomes emotional reactions, or text becomes sound becomes words, and back that story up with descriptions of the way neural networks grow and interact. Â But when you move past the stuff that happens more mechanically, and start trying to understand personalities, creativity, intelligence, etc., it’s basically a giant mystery.

There’s a fair amount of literature on those topics, but my strong sense is (and I want to write a longer, better researched entry backing this assertion up because it’s definitely my opinion) that that research is essentially psuedo-science, in a very particular way. Â It sounds like science, because the researchers form hypotheses, do proper controlled experiments, and find statistically significant results, but if you look at the theories that those experiments are testing, they’re somewhere in between “begging the question” and “making shit up”. Â For instance, (citation needed) there was a study that found that of a group of nuns, the ones who were more optimistic tended to live longer. Â Okay, nice, so a journalist reports “psychologists prove optimism is good for your health”. Â But although that makes a nice headline, we haven’t actually learned anything, because “optimism” is just a word for people who got a certain score on a survey that some researcher made up (in fact, a lot of psychological research consists of building such surveys to provide definitions for various terms). Â Â We don’t actually know if “optimism” is a meaningful description of the way people’s minds work, or whether “optimism” is just the symptom of something else, like a runny nose could mean a flu or it could mean allergies. Â Â Â We don’t have the power to deduce anything about optimism in general.

Likewise nutrition is in the same basic state. Â Michael Pollan in In Defense of Food does a really good job laying out exactly how little we actually know about nutrition. Â Quiz: is margarine or butter healthier for you? Â Answer: not sure, but I’d bet on butter. Â And yet margarine is successfully, to-this-day, marketed to people who would prefer butter but feel obliged, for health reasons, to pass it by. Â Â Â The big problem with nutrition is similar to the big problem with psychology: you can do a study that demonstrates a correlation (feed rats more of a particular nutrient, see how many develop cancer), but we don’t have a theoretical framework powerful enough to draw conclusions about the operation of the entire system. Â Quiz 2: suppose I show you that feeding rats antioxidants reduces cancer risk, and suppose I show you that feeding rats fiber reduces cancer risk. Â What happens if you feed rats both antioxidants and fiber? Â Answer: trick question — not enough information! Â What if — and this kind of complicated interaction happens all the time in cell biology — the antioxidants trigger cellular processes that, combined with the fiber, release a third chemical that actually increases cancer risk? Â We can’t answer that question without performing another experiment. Â So when you step back and try to answer the big questions that people care about, like “is vegetarianism healthy? Â is veganism? Â how about low-carb diets? Â how do I lose weight?” Â you get a lot of conflicting, confusing information, which is why people keep on successfully writing and marketing diet books.

So, back to reductionism. Â Because psychology and nutrition have not been succesfully reduced to biology, it’s an open question about whether or not they can be. Â The question is important, because whether or not you believe the answer is yes determines to a certain extent how you set about doing research. Â For instance, if you’re a reductionist, you probably want to know if “optimism” can be mapped to something in the brain, such as a particular configuration of neurons, whereas if you’re a non-reductionist, you doubt there’s a clear mapping and so treat it as a basic element of research (or come up with your own theory instead — I kind of like “yellow bile” as a basic element of human psychology).

I’m going to go out on a limb and say the answer is “none of the above”. Â I think it’s very likely that concepts that we care about, such as “optimism”, “healthy”, “happiness”, etc., don’t map neatly to underlying physical phenomenon. Â The reason I don’t think we’re going to be able to find neat mappings is because those concepts are in part descriptions of reality but in part value judgments. Â One person’s definition of healthy might be longevity. Â Another person’s definition of healthy might be “able to benchpress 300 lbs”. Â Most people are going to have a mix of those things, with millions of little factors thrown in, such as “how do I feel?” “how do I look?” “how energetic am I when I get up in the morning?” Â You can try to nail down and quantify pieces of that, but you’re going to lose the gestalt of healthiness. Â To me, I think “healthy” and “happy” are like “beauty” — you can debate whether or not something’s beautiful, and there is some element of an objective character to the discussion because people will agree or disagree with each other based on physical evidence, but at the end of the day you can’t prove anything.

So, I don’t think you can “reduce” the kind of questions that nutritionists and psychologists are interested in. Â But neither would I say that they are scientific facts in their own right (yellow bile!) Â Rather than thinking of psychology and nutrition as sciences, I think a better paradigm is to think of them as a branch of design / engineering. Â People think of them as science because the human body and mind already exist and we want to learn about them, but if you think about it, it’s just a coincidence that we have a starting point that already exists… we can still imagine redesigning them from scratch (in theory… in practice, not any time soon…) and, more to the point, we can modify them.

So why do I think psychology and nutrition should really be a branch of engineering? Consider the similarities:

-There is more than one right answer in engineering. Â Is an iPad better or worse than a Lenovo laptop? Â Neither; or rather, it depends on what you’re using them for, and even then it is still subjective. Â Likewise, there are plenty of examples of people with radically different diets living long, healthy lives, and people with radically different psychological makeups and life experiences being happy. Â I’ve read so many flame wars between proponents of one diet vs another, or one set of beliefs vs another, that would just go “poof” if both sides recognized that there is more than one right answer.

-Certain things don’t work. Â If you ignore the laws of physics when architecting a house, it will fall down. Â A laptop produced today runs much much faster than a laptop produced ten years ago. Likewise, certain diets will kill you, as will certain psychological attitudes & beliefs. Â Engineering is subjective, but it’s not relativistic.

-Engineered systems are complex, and must be understood as a series of interactions and tradeoffs. Â The human body and the human mind are considerably more complex than anything engineers have ever architected, so assuming that there are simple laws for describing them seems naive, when you look at the amount of judgment and detail that goes into, say, designing a car engine.

-There is a design / aesthetic component. Â When evaluating the tradeoffs of different solutions, people are going to weight them differently based on their individual values, and that’s totally legitimate.

-You can apply the scientific method to do benchmarks on a design, but a benchmark only tells you so much. Â Examples of benchmarks in engineering: Â How many pounds of pressure can a given structure hold? Â How fast can a database system perform a join of two large datasets? Â Both questions can be answered via the scientific method, but neither will tell you the answer to “is that a good design for your structure / database?” Â For me, this is the most important consequence of thinking in terms of “engineering” vs “science”. Â Much of the research being done in psychology and nutrition seem to be along the lines of benchmarks. Â “What is the correlation between nutrient X and effect Y?” Â “How do people who journal regularly rate their happiness on a scale of 1 to 10?” Â Â You would never design a car through those kinds of tests; at best, they’re useful for evaluating your designs after the fact against a certain narrow set of criteria. Â But that’s really what we want out of those sciences: the ability to design diets, make smart life decisions, be healthy and happy. Â So why are we treating them like a science? Â If you think in terms of engineering, then research becomes about building prototypes, sharing best practices, critiquing design decisions, debating aesthetics. Â You try things, you see what works, when something doesn’t work you ask “why”. Â Â That seems more productive to me than putting a rat or a psych undergrad into yet another controlled study…