If you think about it, the movie is kind of the perfect exemplification of everything the “videogames cause violence” lobby has been going on about. Not only does it glorify video game culture, but the characters in the movie actually progress from playing videogames to having videogame-style fights with real human characters. In one of the opening scenes, for instance, the protagonist Scott is playing a collaborative DDR fighting game with his “fake high school girlfriend” Knives; in the grand finale, Scott and Knives finish off the movie’s “final boss” with the same coordination and moves.

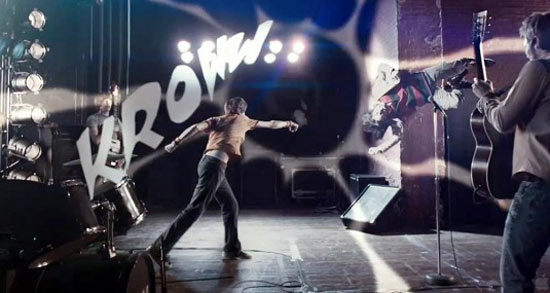

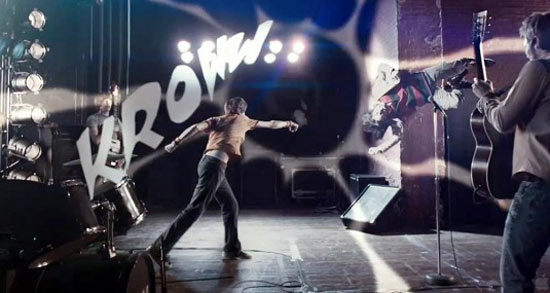

The line between real violence and fake violence is definitely blurred big time. The plot pits Scott against his girlfriend Ramona’s “evil ex-boyfriends”, and one by one he kills them off in highly stylized fight sequences, complete with experience points and “pow” graphics. The reality of the killing is diminished by the retro effects, such as having defeated boyfriends burst into coins, and the evil exes’ somewhat blasé attitude to the whole thing wraps it up. Scott’s initial reaction to learning about the “league” is also jaded disinterest (Ramona tells him that to date her he has to fight her exes; “does that mean we’re dating? Does that mean we can make out?”), but after narrowly surviving a couple fights it sinks in that his life is actually on the line and he freaks, weakening Ramona’s and his growing relationship.

Scott’s own ex, Envy, who is played straight as a real live human, but who is dating one of Ramona’s evil exes, points out to Scott that saying “sorry” doesn’t make up for headbutting her boyfriend so hard he explodes. Scott spends the next scene cradling a cold drink against the bump on his forehead. Is he a serial killer or just playing a game?

My generation grew up hearing about how violence in games and on TV was going to lead to us all going on school-shooting rampages. Now, we’re old enough that we’re the ones writing the characters, and we’re taking a look from the inside at growing up with videogames as a cultural reference. Everyone over 50 knows where they were when Kennedy was assassinated; every nerd under thirty recognizes the music snippet that opens Scott Pilgrim from the title screen of Zelda: A Link to the Past.

A lot of the sell is just straight-up nostalgia. The 8-bit rendition of Universal’s theme music in the movie and the comic spread where Scott and Ramona are making out framed a la the title screen of Sonic the Hedgehog 2 — to pick two random examples — don’t have any real merit beyond pure referential fun. I love it, but I’m also a little ambivalent, much in the same way I am about the first Kill Bill movie: although it raises interesting questions about the societal value of video games and violence, it panders same-said games and violence to hook the audience.

Interestingly, although video game references are woven throughout the graphics, music, and narration, there aren’t that many explicit references to them by the characters themselves. Scott and his friends aren’t hard-core gaming nerds; they’re Canadian wannabe indie-rock stars / unemployed 20-somethings. They grew up with games as a part of their childhood, but they don’t spend much on-screen time playing them. When they do, it tends to be regressive: in the comic books, Scott stays in bed playing when he’s depressed after Ramona breaks up with him (“I have a tiny world to save”), and throughout it’s the least mature characters (Neil, Knives and Scott) who play the most. In fact, it’s not even clear that the rest of Scott’s social circle is that into games at all.

Rather, Scott’s life

is a video-game: he has to advance through the levels, fight bosses, take on challenges, and eventually win to get the girl. I think the real appeal of

Scott Pilgrim is that that’s where we’re at as a generation. We’ve grown up past the point of caring about games vs the real life challenges of relationships, employment, etc., but at some level, part of our minds still resonate with the concepts of taking damage and leveling up.

The most addicting games for me personally were always the ones with the basic plotline of “young hero grows up, takes on challenges, saves the world”.

Zelda is as much a bildungsroman as

A Portrait of the Arist as a Young Man, and for better or worse, the former outstrips the latter in our imaginations.

So the question Scott Pilgrim really raises for me is, what exactly are the merits (and demerits) of seeing your life through the video game lens? Some of the downsides are pretty obvious: the good versus evil thing, the whack-it-with-a-sword strategy. On the upside — and I don’t think this gets nearly enough air time — is the game model of life ambitions and goal achievement. Being imprinted at a very early age that my job is to “save the world” beats the hell out of being taught that my job is to make money, raise a family, buy consumer goods, retire, and die, at least in my opinion. Characters in mainstream TV shows tend to be defined pretty statically via their profession or social circle: e.g., the detectives on CSI, the NYC losers on Seinfeld, the typical American family of [insert show of choice here]. In contrast, videogame characters go from being nonentities in tiny little villages to battling ultimate evil for the fate of mankind. I find the latter a little more inspiring. And — when you look at the scope of the challenges facing mankind these days — probably a little necessary.

Let me qualify that: I’m actually only talking about nerdy videogames, as opposed to GTA or Madden football. What counts as a “nerdy” game? I’m not sure I can do better than “I know it when I see it”, but I think it has to do with the degree of imagination / fantasy involved. A “nerd” I think is someone who spends enough of their time caught up in imaginary worlds that

they don’t develop the social skills to “fit in” in the real one. There’s a high correlation between nerdiness and future greatness (see: any succesful startup founder / scientist / engineer). There’s also a high correlation between nerdiness and dying alone in your parents’ basement. That’s the pro v con of imagination: it allows you to set aspirations beyond the mundane, but the disconnect from the mundane also discourages action in the context of your immediate surroundings — which, at the end of the day, is the only context where action can take place.

Therein lies the real genius and merit of Scott Pilgrim. As the nerds grow up, there needs to be a bridging of the gap between the kid who spent his youth playing Chrono Trigger and the adult taking a role in society. The risk is permanent disconnection between the two worlds — the guy who settles for a boring corporate job during the week, and plays dungeons & dragons with some friends on the weekend — leaving empty contribution and sterile imagination. But what if we actually applied the game concepts to our day jobs? The role and responsibility of being a hero. The primary virtue of courage, and the primary strategy of “leveling up”: improving our “character” attributes to allow us to take on bigger and bigger challenges. Getting off the x-box and playing life instead. Scott Pilgrim gains in levels when he faces his inner demons and makes the hard choices: accepting his past, being honest in his relationships, confronting his fears. And you know what… it works. Sure, it’s a little cheesy when Scott finally confesses his love for Ramona and then gets to pull a heart-pomelled sword out of his chest, but it’s fun, and I’m cheering for him, because it was the right choice and man the music and fight choreography is great!

Scott Pilgrim works for me because it plays the reality game in a sophisticated way. The biggest challenge of drawing a book about someone who goes around poofing his enemies into piles of coins is that in real life, when you punch someone, they don’t turn into a pile of coins. If we’re to buy into Scott’s view of the universe, we have to buy into the reality of his universe. This is where the writing in both the comic books and the movie really carries the day. It isn’t that great, in terms of overall level of zing. There are a lot of very funny moments, but the humor is the kind of humor that emerges naturally from the kinds of interactions that I have with my friends, not the kind of humor that you need a professional writing team to create. For example: “If you want something bad, you have to fight for it. Step up your game, Scott. Break out the l-word.” “Lesbian?” “The other l-word.” “Lesbians?” It’s really not that funny. But by being kind of lame, it creates a believability that makes the characters real and carries them through situations that would otherwise be completely ridiculous. Case in point (and spoiler alert): One of the evil exes has psychic powers, which he has earned because he’s a vegan, and when he’s tricked into consuming dairy he gets taken down by the “vegan police”. Any writing team that can make that scene not descend into unsalveagable farce and take the movie down with it deserves some kind of award.

One of my favorite throw-away lines in the comic books is a narrator’s note that points out that Tamara (a minor character) is Knives’ only friend, “apparently”. That little qualification is a form of breaking the fourth wall, but in a subtle way: it puts the narrator on the same plane as the viewer, reduced to reading between the lines instead of the usual omniscience. It pokes fun at the story itself — ie, the implication is that Knives is a bit of a caricature — but simultaneously implies that the story’s universe has a life of its own that we’re just peering into through the limited window of the comic strip. Another example is Ramona’s exposition of “subspace”, one of the sci-fi-reality plot devices: “oh, I guess they don’t know about that in Canada yet.” That’s the overall tone of Scott Pilgrim in a nutshell — not taking itself too seriously, but at the same time asserting that, plot silliness aside, the characters are real people.

The theory is that playing violent videogames erodes the distinction between fantasy and reality, leading to, for instance, the Columbine massacre. Something’s going on with the reality-fantasy distinction in

Scott Pilgrim, but I don’t think it’s as simple as “erosion.” It’s more along the lines of a redefinition or an augmentation, and it’s very conscious. Although subspace, ninjas, and street-fighter-style combo attacks clearly don’t exist in the real world, I think there’s a level at which viewing life as a “video game” is just as legitimate as any other narrative you choose to tell about who you are and what you’re doing on planet earth. One of my favorite bloggers recently wrote about

viewing life as a dream and yourself as a figment of the dreamer’s imagination. The interesting thing is that you can’t prove that he’s correct or incorrect vs someone who believes in an objective “reality”, but yet there are real world consequences of adopting that perspective.

So at the end of the day I think it’s more of a question of what do you want to choose. When I look at Scott and his friends, what I see is a deep self-absorption, tempered by desire for growth, and a hunger for love and creative self-expression. That’s a fair enough critique of my generation, I think. I don’t think the making-the-right-choices equals beating-the-level analogy is the be-all-end-all perspective on life, but you could do worse. I’ll let my kids play videogames. At least the cool, retro 16-bit ones.

But back to Scott Pilgrim. Having started with the comics before seeing the movie, this was a “are they going to ruin it or make it awesome?” experience for me. I think my verdict is that on its own, the movie lacks a lot of the richness that makes the comic books really great, but that in tandem it adds to rather than detracts from the books, and that even by itself it is still very worthwhile. Also, there’s just a ton of raw payoff in seeing certain scenes live-acted with music. The fight sequence with Matthew Patel, which I’d rate as okay in the comic, is awesome in the movie, as is the bantering between Todd and Scott. And Scott’s band, Sex Bob-Omb, works brilliantly live — Beck wrote their songs for them, and the music is just plain hot. (If you get the soundtrack, you get an 8-bit version of the main fight song, “Threshold”, which is worth the price of admission by itself). Envy’s rock performance in the movie totally does justice to what you’d imagine her singing to be like. The Knives scenes were also great — some of them were a little too over-acted for my taste, but the payoff in certain scenes (trying to “be good” during band practice, Scott rolling off her back playing DDR together, staring sadly through the window, and of course the hair-dying scene) more than make up for it.

The biggest question for me was whether the actors could live up to the comic book characters. Going in, I was afraid that casting Michael Cera (you know, the guy who epitomized the de-masculined adolescent in Arrested Development and Superbad) as Scott Pilgrim was a terrible mistake. It actually worked out really well. He’s not exactly the same Scott Pilgrim as Scott in the books, but he’s close enough, and even more importantly his Michael-Scott blend works in its own right as a character. The same goes for the rest of the cast — they all emerged as almagamations of the actor’s and character’s personalities, but all held together solidly. I especially enjoyed seeing Wallace come off the page — the actor captured the shameless despicableness combined with genuine affection for and mentorship of Scott perfectly.

Speaking of fun, Gideon, the main villain, is also great — the actor really captures the essence of the character, as spelled out in giant block letters in one of the comic-book panels: “WHAT A DICK.” (Best Gideon line from the comic: “Yes! I had a sword build into Envy’s dress in case of emergency! That’s just the kind of guy I am!“) This is a good example of the comic book and movie supplementing each other, actually. Although the movie captures the flavor, it doesn’t go into Gideon’s psychology, whereas the book shows Scott recognizing a bit of himself in Gideon: the part of him that’s trapped inside his own head and sees his succession of relationships as a personal narrative of pain and ego as opposed to seeing his exes as seperate, real human beings. However, what the movie does do is play snippets of “Under My Thumb” by the Rolling Stones, which captures Gideon’s attitude perfectly  and blends it with the indie-rock aesthetic of Scott’s world. Prior to watching the movie I would change stations when the song came on — it always struck me as creepy and off-putting — but now I appreciate it in the context of Gideon’s character: it’s still creepy, but it has a point in the same way that the Imperial March is a fun piece of music in the context of Darth Vader being a bad-ass villain. I did miss the visual from the comic of mind-Gideon having mind-Ramona on a leash: probably wasn’t PG enough for the movie.

and blends it with the indie-rock aesthetic of Scott’s world. Prior to watching the movie I would change stations when the song came on — it always struck me as creepy and off-putting — but now I appreciate it in the context of Gideon’s character: it’s still creepy, but it has a point in the same way that the Imperial March is a fun piece of music in the context of Darth Vader being a bad-ass villain. I did miss the visual from the comic of mind-Gideon having mind-Ramona on a leash: probably wasn’t PG enough for the movie.

Necessarily, the movie falls short in capturing the richness of the character’s interactions with each other over time. The books have the plot set over a span of about a year; in the movie it feels like a week or two. The movie introduces a “battle of the bands” device to tie the plot together and keep it moving, which I thought was a smart choice: you’re going to have to cut the plot down and make changes to succesfully transition mediums, and I thought that pretty much all the decisions made sense, even though the net result was some inevitable loss. I’m not sure how I feel about the much bigger role Knives plays in the movie’s finale compared to the books, even up to the point of almost getting back together with Scott. At the end of the day, though, there needs to be a foil to the Scott-Ramona relationship, and the movie doesn’t have time to develop the Kim and Lisa plotlines so using Knives is the logical choice. I do think there’s a feminist-literature master’s thesis to be written comparing Ramona-in-the-comics breaking Gideon’s shackles and helping Scott put an end to him to Ramona-in-the-movie getting in one nut-shot then getting knocked out, leaving the majority of the dirty work to Knives and Scott. Kidding.

The biggest flaw of the movie, I think, is that the Ramona-Scott relationship never takes on the same level of credibility that it develops in the comic books; the shortened time span and the ruthless editing of scenes that don’t drive the plot forward are necessary to make the movie work, but don’t leave room for organic richness of characterization. One of my favorite sequences from the comic is the beach arc, completely excised, where you really get to see the fluxuations between affection and tension that characterize two people learning to be part of each other’s lives. Since Ramona’s character arc is largely about learning to stay put and hold on instead of constantly running, she loses the most in translation.

On the flip side, you get a giant music-Gorilla battling synthesizer-dragons in a giant auditorium to awesome rock music. I’ll take it.

Scott’s own ex, Envy, who is played straight as a real live human, but who is dating one of Ramona’s evil exes, points out to Scott that saying “sorry” doesn’t make up for headbutting her boyfriend so hard he explodes. Scott spends the next scene cradling a cold drink against the bump on his forehead. Is he a serial killer or just playing a game?

Scott’s own ex, Envy, who is played straight as a real live human, but who is dating one of Ramona’s evil exes, points out to Scott that saying “sorry” doesn’t make up for headbutting her boyfriend so hard he explodes. Scott spends the next scene cradling a cold drink against the bump on his forehead. Is he a serial killer or just playing a game?

The most addicting games for me personally were always the ones with the basic plotline of “young hero grows up, takes on challenges, saves the world”. Zelda is as much a bildungsroman as A Portrait of the Arist as a Young Man, and for better or worse, the former outstrips the latter in our imaginations.

The most addicting games for me personally were always the ones with the basic plotline of “young hero grows up, takes on challenges, saves the world”. Zelda is as much a bildungsroman as A Portrait of the Arist as a Young Man, and for better or worse, the former outstrips the latter in our imaginations.

and blends it with the indie-rock aesthetic of Scott’s world. Prior to watching the movie I would change stations when the song came on — it always struck me as creepy and off-putting — but now I appreciate it in the context of Gideon’s character: it’s still creepy, but it has a point in the same way that the Imperial March is a fun piece of music in the context of Darth Vader being a bad-ass villain. I did miss the visual from the comic of mind-Gideon having mind-Ramona on a leash: probably wasn’t PG enough for the movie.

and blends it with the indie-rock aesthetic of Scott’s world. Prior to watching the movie I would change stations when the song came on — it always struck me as creepy and off-putting — but now I appreciate it in the context of Gideon’s character: it’s still creepy, but it has a point in the same way that the Imperial March is a fun piece of music in the context of Darth Vader being a bad-ass villain. I did miss the visual from the comic of mind-Gideon having mind-Ramona on a leash: probably wasn’t PG enough for the movie.