Utopian revolution? What does it look like?

Albert Wenger from Union Square Ventures wrote a blog post in favor of a utopian revolution that I’ve been thinking a lot about the last couple days.

To summarize, his point is basically: a) the current political and economic system isn’t working, b) we don’t have a concrete vision of what to replace it with, c) let’s aim big (total eradication of poverty while living in harmony with the environment on a global scale), because d) we now have the technology to pull it off over the next few generations.

His suggested approach is along the lines of guaranteeing income and internet access for everyone, and decentralizing governmental power to cities, which he’s putting out as a vague roadmap to be fleshed out through continued conversation and research.

My initial reaction was intense enthusiasm, because I generally agree that things aren’t working and that incremental change isn’t going to get there, and because I’m a believer in big ambitious crazy goals.

I’m still positive, but I’ve been thinking about what’s really wrong with the status quo, why it’s intractable, and what a solution would have to look like.

My basic sense is that high-tech, highly-networked capitalism is structurally flawed. The problem is that there is too much competition for too few ecological niches. As transportation and communication technologies improve, markets move from local to global, letting a single player provide for the entire system.

For instance, in an agrarian economy, food production provides an ecological niche for a huge percentage of the population. In an industrialized economy, food production is taken care of by a tiny fraction of the population. Or take entertainment… back in the day, musicians only had to compete with people within a few miles of them. Now, they have to compete with every single musician in the world. Or for another example, taxi drivers are not going to be employed once Google’s self-driving cars become mainstream.

The counter-argument to this is that as technology improves, it creates new niches that didn’t exist before. For instance, “blogger” is now a role that people can fill that didn’t exist twenty years ago. It’s definitely true that technology creates opportunities as well as destroying them, but I suspect that the rate of destruction is higher than the rate of creation. The way new opportunities get created is by enhancing the amount individuals consume. However, consumption can’t go up indefinitely, because there’s a hard cap on the number of hours in a day people can spend as consumers. Moreover, there’s a huge spiritual cost to an economy that depends on people constantly raising their standards of consumption, as advertisers try to convince people to care about increasingly trivial things.

I suspect that the situation in terms of job destruction is worse than the economic numbers show. I’ve been watching The Office lately, and while the show is a comedic exaggeration of corporate culture, there’s a big grain of truth which is that a huge percentage of time spent in office jobs is actually creating no value. I think there are probably millions and millions of jobs that could disappear overnight without a big impact on the total level of production. These jobs appear to exist for now, but the incumbent corporations that subsidize them are increasingly being beaten out by startups that aren’t burdened by non-productive workers.

So the fundamental problem with a capitalist system is that as technology improves, it increasingly renders the majority of the population irrelevant to the production of things that society wants. My belief is that the 99% vs 1% dynamic is a natural outcome of capitalism taken to its logical limit, not the result of a few greedy politicians and bankers. In a high tech society, we only need 1% of the world to be productive, and in pure capitalism, that 1% gets to walk away with all the money, which translates into all the power. (That translation can be slowed down via things like campaign finance reform, but it’s hard to imagine the kinds of restrictions we’d need to put in place to really take money out of politics altogether — we’d basically have to ban advertising.)

So. What to do?

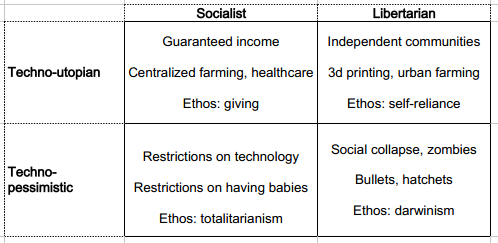

Here’s a 2 x 2:

The techno-utopian socialist answer is: divorce production from survival / ability to be happy. We guarantee food, shelter, medical care, etc., for everyone, taking advantage of the dynamic that’s causing the problem in the first place: that a small percentage of the population can provide for everyone else. This seems to be more or less what Albert Wenger is suggesting.

The big challenge with this approach is that it requires a cultural sea-change: we basically need to completely abandon the capitalist social contract, which is “I work == I deserve a seat at the table.” That means forging a new social contract. Forging a new contract is really really hard; it generally requires some kind of sweeping self-identity narrative revolution. That revolution could happen; there are communitarian and gift-economy ideas floating around that might be able to be forged into the necessary materials for a new social contract. The basic story would be something like “we live in a society of plenty, let’s compete to see how much we can contribute to each other and the world”.

This is similar to the ethos behind socialism and communism, which don’t have a particularly impressive historical track record. However, when most of the large-scale communist experiments were happening, the world didn’t have the coordination and production technology to actually create wide-scale abundance, whereas with the internet, it might actually be possible. The main lesson to take from the failure of communist regimes is that abundance is absolutely a precondition for any economic system that’s based on a wide-scale giving ethos. “From each according to his abilities, to each according to his needs” only works if people actually believe that society can live up to its end of that bargain.

Even with techno-utopian abundance, there’s still the question of political enfranchisement. In a world where the labor of 1% provides for the material needs of 99%, there’s a huge risk of a two-tier society where the producers have all the power, and the remainder don’t feel they have a social role, even if their direct survival isn’t threatened. I’m not at all sure how this scenario plays out and if there’s a stable, good state to aim for.

Switching gears a bit, the techno-utopian libertarian answer to the flaws of capitalism is: de-centralize the ability to be self-sufficient. Individual communities regain the ability to fully provide for themselves via small-scale production technologies. The goal here is being on-the-grid but not dependent-on-the-grid. Making this scalable would involve the widespread use of technologies like 3d printing and hydroponics / urban gardening. This solution works because small communities now have an opt-out option from the capitalist system: they can provide for themselves, so no longer need to be providing a globally-useful good or service.

The advantage of this approach is that the struggles of surviving as a community provide a meaningful life script for individuals. There’s no need to reinvent the social contract, because the “I work == I have a place at the table” equation still holds. Moreover, there’s a natural culture fit between this approach and America, since America’s westward expansion, which shaped much of its subsequent culture, occurred under similar conditions of small, self-reliant communities.

I see two main challenges with this approach. The first is that it doesn’t provide well for global coordination / tragedy of the commons issues. By decentralizing people’s identification away from humanity and towards their own communities, it probably makes ensuring cooperation on issues like the environment harder. The second is that making the transition will be significantly easier for richer communities than poorer ones; the rich communities have the access to the resources and technology to bootstrap themselves. This is problematic because the poor communities are the ones most at risk of failing in the current economic system.

Okay, moving to the non-techno-utopian quadrants. I won’t spend much time on them. I think both quadrants could be feasible, stable outcomes, but both involve a lot of dead bodies. I’m a technologist, so I prefer to take a utopian approach and fight for a solution that leads to a high level of human life, happiness, and freedom.

Anyway, my preferred answer, I think — although I’m just thinking through this now, so this is probably fluid — is a mixture of techno-utopianism and techno-libertarianism. Both visions of the future have major challenges, but I think they serve to complement each other’s challenges well.

Techno-libertarianism serves as a good check on the centralization demanded by techo-socialism. By providing individuals with a viable “opt-out” option, it compels the system architects of socialism to provide a good deal, both politically and economically, to participants, because they have to compete with individuals just relying on themselves and their local communities.

Techno-socialism helps with the bootstrapping and coordination issues of techno-libertarianism. By providing centralized disbursal of resources, it evens the gap between poor and rich communities trying to become independent. And by providing valuable social services, it becomes a meeting-point where issues of global coordination can be resolved.

Anyway, I think there’s a ton more to do to flesh out what this kind of world could look like. But the idea of something on the intersection of the two approaches is exciting to me.