jComponent: javascript UI library

Just released and gave a presentation on jComponent, a library I’m developing. Â I’ll write a longer post later explaining the thinking behind it in more depth, but for now, here’s the slides and the github link.

The event I presented at was hack ‘n tell, which is pretty awesome — if you are in the NY area you should come check out the next one. Â My favorite presentation today was a demonstration that CSS 3 + html is actually turing complete (via building an implementation of Rule 110) — you have to turn the crank by hand (via pressing tab and space), but it computes!

Hack of the day — contact manager

I want a nice way of keeping track of who I haven’t talked to for a while, so I don’t fall out of touch with people. Â Should be pretty easy, with all our contact information online.

Somewhat surprisingly, I wasn’t able to find anything I liked.  The closest I came was https://gist.com/, which is a cool tool to see all your contacts from all your social networks in one place.  But it didn’t have the one feature I really want — the ability to sort by the last time I contacted a person divided by the rough frequency at which I’d like to stay in touch with them.

So, I hacked together this:Â http://www.joshhaas.com/contact/. Â It’s primitive, but it also does exactly what I’m looking for. Â If anyone knows of a professionally-maintained tool that can do what my thing does, please let me know!

I built it using google’s contact data API, using the javascript library that they provide for accessing it. Â I was disappointed in the quality of the library; the javascript version is lagging behind the most current version of the API, and there isn’t solid and accurate reference documentation. Â Does anyone know what the deal is with this? Â Is Google abandoning the javascript library? Â That would be too bad, because Google’s data protocol is complicated enough that writing raw http/xml handling code would be very painful!

Open problem: I can’t host it on Google App Engine because authentication breaks. Â I assume it has something to do with the fact that the data API recognizes GAE referrer URLs, and maybe something to do with me using an older version of the API (1.0 instead of 3, because the javascript library doesn’t work with later versions). Â Haven’t figured out a workaround yet, so I’m hosting it on slightly slower shared hosting for now.

Thoughts on ‘Inside Job’

After seeing the movie, I’m very interested to hear what the reaction is.

Part of it is going to center around sorting out the facts of the matter. It’s hard to tell just from watching it how much of the movie was an excellent simplification of complex issues, and how much was an over-simplification. The rebuttals are starting to come in and it’s going to get messy. My personal guess is that the story the movie tells is accurate at a mile-high view and much messier near the ground, which in part explains how something like this can happen in the first place. In the middle of it, it’s a lot harder to see.

One of those mile-high truths is that the finance sector, by and large, doesn’t have a strong moral compass, stretching from the CEOs down to the analysts. It’s particularly bad in finance because there’s so much opportunity, but in my personal experience it is very easy to graduate from a top university without learning a thing about ethics and morals, which leads to a bunch of bright young people entering the real world without any societal inoculation against that kind of corruption.

I got lucky — I was raised by parents who weren’t complete moral degenerates, and then my tenure in finance was spent working for a firm whose business model is to profit off of long-term integrity. One of the things I learned there, actually, is that integrity is practical — it’s not a matter of real world gains vs nebulous ethical consequences, it’s a matter of short-term gains vs long-term suffering. But I’m not sure how many people entering the workforce have been taught to see it that way.

What I really want to see is some form of secular moral education. Traditional moral education has been pretty much systematically eradicated from the educational system, for some good reasons: it tended to be dogmatic, close-minded, and logically dependent on unprovable suppositions (i.e., the truth of the bible). But there’s a gap where it used to be, and I think the intellectual tools exist to fill the gap with something that makes sense. I.e., some kind of open-minded, dialogue-based, rational discourse about really what it means to be an effective, ethical member of society.

To be clear, I don’t want more pop-philosophy lectures about pushing a fat person in front of a train. For this to be at all useful, getting an ‘A’ can’t be dependent on things like an intellectual understanding of Rawls’ theories, or an agreement with group / teacher sentiment. Rather, it needs to reward genuine, open-minded, personal wrestling with real issues. It’s hard, but I think we can do this. I believe that as a secular, rational society, there are things we can still agree on in terms of integrity and other values to form the curriculum. And in terms of creatively teaching it, I think there are possibilities.

Bastille Day

[This is a half-written story. Not quite sure how I want to finish it. If you have thoughts, let me know.]

Claire huddled in her chair, pulling her blanket around her, to shut off both the cold and the screaming next door. An itching in her throat made her spit a few drops of saliva onto her rumpled nightgown. In the bed next to her, Henry moaned gently in his sleep. It was 4 am, and Claire compulsively scratched her arm where the doctors had injected her with the serum yesterday. Could she feel it working inside her or was it just her imagination? She shivered, not completely sure herself whether it was from the cold, the anticipation, or an unaccountable fear.

Claire had consented to the treatment, her aging muscles barely cooperating with pen as it scritched her name on the forms, but it was really just a formality: recent judicial decisions had mandated treatment for those too far gone to decide in their own rights, and no one in the homes consciously decided to forgo it. Claire watched the news, on the days the nurses left the little TV set she could see from her bed to the right station, and she knew that there were others out there who, admidst some political controversy, voluntarily rejected their right to life, but they seemed to live in a different world. A world where affluent relatives tearfully surrounding their bedsides, as gentle breezes blew through the open windows of their bedrooms. True, the breezes carried the distant echo of protestor’s shouts, but even those blended in with the peaceful spring air that lulled the beds’ occupants towards a permanent nap. Claire shook herself, turning off her imagination before before loneliness and pain could shut her down. In the real world it was fall outside.

The next few days passed by with Claire drifting in and out of consciousness, her dreamy musings interrupted only by the occasional cups of mushed vegetables and medical jello the nurses brought at random intervals. She ate, more to keep her mind occupied than for anything else, and waited.

She awoke one morning with the unusually firm conviction that it was Tuesday. Yawning, she stretched her bones a little and tried to account for the strange sensation she felt in her head. It was only until after the other residents had woken up that she placed it: the absence of a headache. She closed her eyes quickly, shaking her head back and forth until the flash of strange emotion faded away. Heart still pounding faster than usual, she took to her Sudoku with concentration, going through puzzle after puzzle without losing steam. She ate an extra large helping of the white-meat entree that night.

On Wed, a volunteer for the Elderly Rehabilitation Association came by with an info kit and some forms to fill out. Claire pretended to be more out of it than she was to avoid conversation, and pushed the kit aside, not wanting to think about it. Later, two nurses helped her out of her bed and rolled her down the hall to the examination room, where a harried visiting doctor shined a light in her eyes, probed her arm muscles, tested her saliva, and then made some curt notes before sending her on her way. On the way back to her room, she passed the next old person being wheeled to their examination, and, perking her head up, she noticed an unusual buzz of activity: more wailing, more muttering, some nurses moving around with an unusual briskness while others seemed to be slumping despondantly. Even the most dimly conscious of the eldery stirred more than usual as if they could tell through their haze that something was in the air. Raised voices on the telephone went back and forth in an indistinct argument, and it looked like someone had cleaned the usually musty linoleoum floors and counters, although the folders and pieces of medical equipment were unusually scattered. Claire returned to her room and watched some TV.

By Fri morning, Claire could no longer ignore the fact that she was feeling better than she had in years. Throughout the day, the nurses, who had obviously just been trained on this themselves, came by to assist her with various leg and arm excercises, almost completely atrophied muscles slowly and painfully waking up. Although the skin on her arms was still blotched and saggy, it seemed to be pinker instead of its usual sallow yellow, and next to her, Henry surprised her by uttering a complete sentence, something about the television show that was playing in the background. Although it had been months since the last time Claire joined the communal activities in the group room, today she had the nurses wheel her over, and as she haltingly interacted with her fellow residents she picked up an undercurrent that — bizarrely out of context as it seemed — could only be described as excitement.

When she took her first halting steps into the sunlight — real, honest-to-god sunlight — Claire felt a buzzing numbness over her entire body. Her heart, beating at a rate that would have killed her a week ago, hyperventilated with a rush of sensations that shifted too quickly for her to give names to. She walked slowly forward, a step at a time, not sure where she was going or why, dimly clutching onto the phone number and address she’d removed from the ERA info kit.

[Not sure where to go from here. I’m kinda toying having her get hit by a car in a minute and ending the story, but that feels a little cheap. What I really want to do is zoom out and look at this whole thing from a much bigger panaromic view, really explore some of the interesting consequences, but I’m not quite sure how to do that.]

Cleaning out the crap

So lately I’ve been feeling a pretty strong desire to write. The funny thing is, it seems to be combined with an equally strong lack of anything to say. I don’t think that’s due to an innate lack of inspiration… rather, I think there’s some quite decent writing in me buried under multiple layers of crap.

Insert some mumbled academic point about perfectionism here… what I mean to say is that the only way through to the other side is to just get all the crap out of my system. It’s a rarefied form of pure agony to sit in front of a blank screen and type garbage, but the upside is that it’s probably good exercise for your fingers, not quite (but almost) up there with piano.

Anyway, since the only way to really be sure you’ve exorcised a demon is if the entire neighborhood witnesses it returning to hell, here are a few chunks of crap I came up with:

1:

Setting the scene: The Charles river. You’re standing on the bridge, concrete and cars going by behind you. Got your headphones on, “I am an American” pumping in your ears. An impossible football throw away, another bridge, stone and mortar, arcs.

The cast: Me, myself, and I. And an iPod.

The plot: Going for a jog. In another month it will be sweaty hot — as is the air barely accepts the heat I’m dissipating.

Not in the scene: a girl, 20 years old, standing by the window of her dorm, on a cell. You don’t know who she’s talking to, but it isn’t someone on campus.

“fours are up!” I call, diving to the ground.

2:

Pink panda bear pansies . Purple petunias eating cheese. Nazi monkey fish liver pirates. Rumplestilkin baby sneeze. These and these I stir together — these and these I stir apart; wander weather wilters better; blink twice and I’ll break your heart.

3:

Mr. Lipstaticker lived on a drive at the end of a long road at the end of a long, windy town. Good day! Good day! He’d say, and walk, mockingly, on by, while all the children stared and cried.

4:

Single, she stood by the window, waiting. Her name was Annie. Out the window, she saw a car drive by. In it — not the guy she is waiting for. She sighs. Stands, and paces across the room, only to turn back at the sound of an engine — no, a stranger’s headlights cresting the hill. Could he have been seriously hurt? Would that be worse?

5:

Whaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaateeeevver. That’s what she said. Well, not to his face, anyway — not yet — but with her friends, getting drinks on a quiet saturday night, she would bitch about his cheapness, about his looks, about the neighbor’s grunts heard through the flimsy walls of the apartment they shared together.

6:

Once upon a time, there was a boy. I’d like to think he was the silent hero type, but actually he was really more the silent awkward — so out of touch with reality he could barely tell the difference between videogames and life. Well, except that he liked videogames.

We find him sitting in his room, the summer before going to college, staring at his computer and typing an entry on his webpage — I think this preceded blogs, or if it didn’t, he hadn’t heard of them. (Well, there was Xanga, but that was just for the nerdy Asians). He’s upset, because he’s been trying to clean up his room to get ready for college, which looms in front of him like a giant blank– nothing, nothing at all, like the thing in the Neverending Story where the world is falling apart and when you look at it there’s nothing to put your eyes on. What he can see is that every book that goes into the box is himself dying a little bit. He can still taste Italy at the back of his mind, and the bitter-sweet finale of high school leaves him with a strange… love? He feels lost, left out of some vast cosmic secret, shown a glimpse that the world is much bigger than he can ever wrap his arms around.

And then — he’s there. The pure pause of exhilerating strangeness the night before — an unfamiliar dusky landscape that he’ll soon imprint so deep in his brain he’ll never again be apart from it — and then the morning, sleepless, excited, so bright in the light of the fading summer. Move in — taking boxes up stairs, the smell of poster gum in heat. He doesn’t remember his parents leaving.

There’s a peculiar shift when your life changes, as your mind adjusts itself to the complete lack of the familiar. Soon enough you can stop seeing things again, because knowledge reasserts itself, but there’s a gap between the stasis of one reality and the fixedness of the next. It persists, in little cracks and edges, for maybe about six months.

What I really want to do is find those cracks again, plunge in, break it open, live, live, live! Always keep running, always keep moving, never let the familiar imprison you. What would it be like to always be traveling?

And there must be something at stake. People. If you don’t care about people, what is there to care about?

I love you, friend. I love you, I love Harvard, I love my brother, the Charles, my memories of Ashland and the Wisconsin arboretum and devil’s den in the rain. I love you, awkward moment — frozen space of new (if unpleasant) possibilities. When will the rains come? What will wash away the veil of the ordinary from this world? How do we free ourselves from the mundane? What is the path? What is the key? Why do the books and games and stories and songs that point the way become our very prisons? Help, damn it, help bust free of the chains of our own weakness and fear and heartlessness. Put things at stake! PUT THINGS AT STAKE! Without it, life is lost — cheapened, by being preserved. A strawberry stale in the fridge (not the beautiful loss of the dandelion dried on the windowsill). Please, oh lord, oh god — the other that is the reality — the gap between where we are and where we want to be: the silence that swallows speech: the shadow, the hollow men, the brainless smug intellectualism that makes you think you understand when you understand nothing, nothing, nothing at all. Alas, the world has died, and we but trod upon the grave of its remnants, the filthy fucking grave, the empty pit. Why do we take the pills? Why do we drink the wine? Gorge ourselves upon bloated sawdust? What promises were made, that we seek to redeem in this way?

That’s what I want to write. I want my words to pierce the veil in thought, to draw the love, to break the grasp, silent, sodden, deadening — that the world has on you. I want to feel and I want everyone who reads me to feel, to feel miserably, to feel terribly, to feel like they’ve been torn and in their tatters can rise again as real people. God damn all silent hypocrisy. God damn the system. Where is the words that will make it dissolve? What is the book? Where is the reading? Can music free? Can the food that feeds you be the food that kills you? What I do know is that there is nothing I know that is not in the knowing of it the deepest poison.

Words. Damned, pitiful words. What are they, against the overwhelming stasis of the mind? Merely feeders, at best, syncophants that pitch… pitch, on to the flame. And at worse, incohate babble. Useless drivel. Empty times new roman font on a white background, size 12.

7:

What I’m trying to say.

I’m not quite sure how to say it yet. I’ll throw out a few words, and see how far they take me. I want to make the point — be it through essay, stories, poems, songs, I dunno the wherefore or therewhat — that 99.95 of the fucking time we spend our lives not actually living in reality but trapped in a mental bubble. All evil comes from the fundamental confusion of thoughts with that which thoughts reference. I can say it, but even as the words leave my mouth they become empty symbols, the map and not reality. Don’t eat the fucking menu! Don’t, for the love of god, eat the fucking menu! I want you to hop in your car, drive down the street, go into the restaurant, barge into the kitchen, and lick the chicken grease off the fucking counters — just DO not EAT the FUCKING menu!!!!!! Please.

It’s for you, not for me.

I mean it.

I love you.

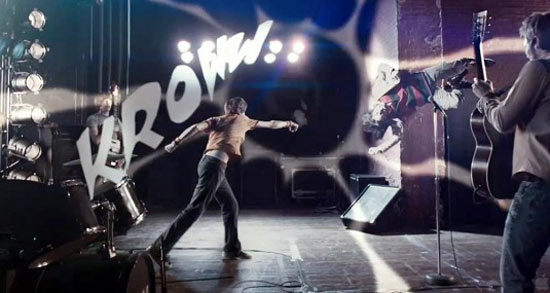

Scott Pilgrim vs Reality

Scott’s own ex, Envy, who is played straight as a real live human, but who is dating one of Ramona’s evil exes, points out to Scott that saying “sorry” doesn’t make up for headbutting her boyfriend so hard he explodes. Scott spends the next scene cradling a cold drink against the bump on his forehead. Is he a serial killer or just playing a game?

Scott’s own ex, Envy, who is played straight as a real live human, but who is dating one of Ramona’s evil exes, points out to Scott that saying “sorry” doesn’t make up for headbutting her boyfriend so hard he explodes. Scott spends the next scene cradling a cold drink against the bump on his forehead. Is he a serial killer or just playing a game?

A lot of the sell is just straight-up nostalgia. The 8-bit rendition of Universal’s theme music in the movie and the comic spread where Scott and Ramona are making out framed a la the title screen of Sonic the Hedgehog 2 — to pick two random examples — don’t have any real merit beyond pure referential fun. I love it, but I’m also a little ambivalent, much in the same way I am about the first Kill Bill movie: although it raises interesting questions about the societal value of video games and violence, it panders same-said games and violence to hook the audience.

The most addicting games for me personally were always the ones with the basic plotline of “young hero grows up, takes on challenges, saves the world”. Zelda is as much a bildungsroman as A Portrait of the Arist as a Young Man, and for better or worse, the former outstrips the latter in our imaginations.

The most addicting games for me personally were always the ones with the basic plotline of “young hero grows up, takes on challenges, saves the world”. Zelda is as much a bildungsroman as A Portrait of the Arist as a Young Man, and for better or worse, the former outstrips the latter in our imaginations.

Therein lies the real genius and merit of Scott Pilgrim. As the nerds grow up, there needs to be a bridging of the gap between the kid who spent his youth playing Chrono Trigger and the adult taking a role in society. The risk is permanent disconnection between the two worlds — the guy who settles for a boring corporate job during the week, and plays dungeons & dragons with some friends on the weekend — leaving empty contribution and sterile imagination. But what if we actually applied the game concepts to our day jobs? The role and responsibility of being a hero. The primary virtue of courage, and the primary strategy of “leveling up”: improving our “character” attributes to allow us to take on bigger and bigger challenges. Getting off the x-box and playing life instead. Scott Pilgrim gains in levels when he faces his inner demons and makes the hard choices: accepting his past, being honest in his relationships, confronting his fears. And you know what… it works. Sure, it’s a little cheesy when Scott finally confesses his love for Ramona and then gets to pull a heart-pomelled sword out of his chest, but it’s fun, and I’m cheering for him, because it was the right choice and man the music and fight choreography is great!

So at the end of the day I think it’s more of a question of what do you want to choose. When I look at Scott and his friends, what I see is a deep self-absorption, tempered by desire for growth, and a hunger for love and creative self-expression. That’s a fair enough critique of my generation, I think. I don’t think the making-the-right-choices equals beating-the-level analogy is the be-all-end-all perspective on life, but you could do worse. I’ll let my kids play videogames. At least the cool, retro 16-bit ones.

The biggest question for me was whether the actors could live up to the comic book characters. Going in, I was afraid that casting Michael Cera (you know, the guy who epitomized the de-masculined adolescent in Arrested Development and Superbad) as Scott Pilgrim was a terrible mistake. It actually worked out really well. He’s not exactly the same Scott Pilgrim as Scott in the books, but he’s close enough, and even more importantly his Michael-Scott blend works in its own right as a character. The same goes for the rest of the cast — they all emerged as almagamations of the actor’s and character’s personalities, but all held together solidly. I especially enjoyed seeing Wallace come off the page — the actor captured the shameless despicableness combined with genuine affection for and mentorship of Scott perfectly.

Speaking of fun, Gideon, the main villain, is also great — the actor really captures the essence of the character, as spelled out in giant block letters in one of the comic-book panels: “WHAT A DICK.” (Best Gideon line from the comic: “Yes! I had a sword build into Envy’s dress in case of emergency! That’s just the kind of guy I am!“) This is a good example of the comic book and movie supplementing each other, actually. Although the movie captures the flavor, it doesn’t go into Gideon’s psychology, whereas the book shows Scott recognizing a bit of himself in Gideon: the part of him that’s trapped inside his own head and sees his succession of relationships as a personal narrative of pain and ego as opposed to seeing his exes as seperate, real human beings. However, what the movie does do is play snippets of “Under My Thumb” by the Rolling Stones, which captures Gideon’s attitude perfectly  and blends it with the indie-rock aesthetic of Scott’s world. Prior to watching the movie I would change stations when the song came on — it always struck me as creepy and off-putting — but now I appreciate it in the context of Gideon’s character: it’s still creepy, but it has a point in the same way that the Imperial March is a fun piece of music in the context of Darth Vader being a bad-ass villain. I did miss the visual from the comic of mind-Gideon having mind-Ramona on a leash: probably wasn’t PG enough for the movie.

and blends it with the indie-rock aesthetic of Scott’s world. Prior to watching the movie I would change stations when the song came on — it always struck me as creepy and off-putting — but now I appreciate it in the context of Gideon’s character: it’s still creepy, but it has a point in the same way that the Imperial March is a fun piece of music in the context of Darth Vader being a bad-ass villain. I did miss the visual from the comic of mind-Gideon having mind-Ramona on a leash: probably wasn’t PG enough for the movie.

The biggest flaw of the movie, I think, is that the Ramona-Scott relationship never takes on the same level of credibility that it develops in the comic books; the shortened time span and the ruthless editing of scenes that don’t drive the plot forward are necessary to make the movie work, but don’t leave room for organic richness of characterization. One of my favorite sequences from the comic is the beach arc, completely excised, where you really get to see the fluxuations between affection and tension that characterize two people learning to be part of each other’s lives. Since Ramona’s character arc is largely about learning to stay put and hold on instead of constantly running, she loses the most in translation.

How do you think about how you should live?

Lately I’ve been thinking about the yardstick problem in regards to how to live a good life. The problem is basically, how do you measure what good is? What’s the standard you use to compare one way of living life to another way of living life?

At some level, it’s pretty obvious that if you have to ask the question, you’re thinking about it the wrong way. I don’t know all that much about the true nature of happiness, but I’m pretty sure that any frame of mind where you’re rating one life against another is not conducive to it — that kind of comparison, weigh-and-evaluate mindset is pretty radically disconnected from the things I associate with wisdom and happiness, such as living in the moment, acceptance, spontaneity, and the like.

But there’s a practical problem with ignoring the question, which is that pretty much anything you choose as the direction to go in requires some commitment and effort, at least if you’re talking about living a life that’s more than just being a coach potato. You can arbitrarily pick something, I suppose, but I find that at least for me I have to have some amount of conviction that my direction is “right” or else I find myself wavering and reversing. I’m not talking about the difference between, say, deciding to help people by becoming an environmental activist versus becoming a doctor, which I think is just a matter of finding the best alignment between your talents, interests, and opportunities; I’m talking about the foundational view of reality that makes “deciding to help people” a worthwhile or worthless path to pursue.

The way I see it, there are a few different competing frameworks for how to even think about what makes for a good life, all of which are compelling and hard to reconcile. (There are also some more-or-less obviously shitty ones, such as trying to acquire as much money / fame / power as you can, drugging yourself via mindless entertainment and idling the years away til you die, etc.) I won’t try to give a fantastic taxonomy, but to give you the flavor of what I’m thinking about, here are some that come to mind:

-The heroic. Good = good; the fulfilling life is adopting a righteous cause, and then taking some names and kicking some ass. There are a lot of variations on this, depending on what you think makes a good cause, and depending on whether your view of a hero looks more like Martin Luther King, Jr. or like Jack Bauer. But the commonalities are that fulfillment comes from being on the side of the angels, and success is measured in outcomes (number of [people/species] [helped/saved/converted/liberated]). I think this context has a lot of deep-rooted psychological power… e.g., Joseph Campbell’s ideas in The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

-The artistic. Good = creation, expression, authenticity, beauty. The fullest expression of your humanity is to bring things into being, to create new patterns and forms never before seen, to rise beyond the mundane by creating meaning. I think one of the best expressions of this I’ve encountered is in Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

-The spiritual. Good = transcendence, oneness, bliss, seeing the interconnectedness of all things. Peace, meditation, insight, and wisdom.

-The evolutionary. Good = growth, self-improvement, achieving your desires and by doing so helping creation expand. Life is a series of outcomes, which are neither good nor bad intrinsically; joy is learning the patterns behind the outcomes and adapting your behavior to get more and more efficacious as you grow in intelligence, power, and wisdom. This is one of the most compelling contexts for me, and a lot of my thinking about the yardstick question comes from seeing myself over the last two years adopt this more and more, and wrestling with the incongruities between this context and my old patterns of belief. A lot of my thinking around this context has been shaped by stevepavlina.com, as well as by my current employer.

-The rational. Good = knowledge, wisdom, understanding. Related to the artistic, in that the primary good is the output of your mind, not the way you live your life. It’s the philosopher versus the painter, or the scientist versus the novelist.

I’m sure there are others, but those are the main ones that I personally find compelling. They’re also damn hard to compare, both in terms of framing up the contrast and in terms of the actual decision. How do you stack writing the great american novel up against curing cancer? Is the life of mind what’s important, or the life you lead every day? You can sometimes evaluate the achievements of one context in the currency of another, as in when art is defended in terms of its political or human impact, but that always feels like it’s at least somewhat missing the point.

Of course, they aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive, which to me actually makes it even messier: you could — I guess — evolve and grow more powerful via art, or do good via a spiritually practice. There are also values that cut across the different contexts, interacting with each of them in different ways: freedom, rising beyond the mundane, fitness-for-a-purpose, and finding universal principles, to give some examples. At the end of the day, though, my experience is that I find the different contexts mutually undermining. When I’m in an evolutionary mindset, I feel like I’m giving something up in terms of the heroic and the artistic; if I’m studying and writing philosophy, I wonder if it’s worth anything if it doesn’t make my day-to-day life better.

Moreover, all of the perspective seem vulnerable to the “so what?” question. The heroic falls apart pretty quickly: okay, so you saved two people’s lives, but in eighty years they would be dead anyway. Likewise, you created a great piece of art, but at the end of the day, it will be forgotten. Evolution, whether you’re thinking on the personal or species level, has its own encounter with entropy. Spirituality doesn’t hit the all-things-will-end wall as obviously, but there seems something sterile about deriving value from an experience that from the outside is indistinguishable from someone in a coma.

Or anyway, that’s the cynical perspective. I’m not saying it’s right, but what it does show is that there are certain premises you have to take for granted to make any of the contexts stand up. That isn’t surprising to me, since one thing I think I believe is that all “truths” about existence and the meaning of life are created by people in conjunction with reality, not derived from reality without one’s active participation. But it does beg the question, okay, so on what basis would you choose to believe one or more of those premises? Why choose to have faith in any of them?

The answer I’ve assumed since I first started thinking about it — and this is the heart of the matter — is that you want to have faith in premises about reality because that’s the path that leads to happiness. It’s a natural conclusion to reach, because the way I think most people get here is that they notice they are unhappy, ask themselves why, start thinking about the meaning of life, realize that you can’t just logically deduce it, and conclude that you need to take on faith some empowering, happiness-giving, view of reality because otherwise you’re going to spend your life as an existential wreck. So then, when you think about which premises and which context you want to adopt for yourself, it becomes a question of picking whichever one makes you happiest.

That sounds pretty logical, and I don’t doubt some people do fine by it, but in practice it just hasn’t been clicking for me. The problem with it is that happiness, which is the meta-context I’ve been using to evaluate the various premises, actually really sucks as a basic thing-to-want-out-of-life. Now to be clear, “happiness” can mean a lot of things to a lot of people, but I’m using it in the most generic, inclusive sense: that of everyday experience having some kind of a positive quality to it, whatever exactly that positive quality really is. This kind of happiness, is bad as a meta-goal because asking “what will make me the most happy?” is pretty much guaranteed to make you unhappy at the end of the day. By making the primary criterion the quality of your experience, you’re assuming a solipsistic reality: “your experience” narrows the universe to the contents of your own head. Although I’m not making an ethical claim that solipsism is bad (because ethics comes much further down in the figuring-out-the-meaning-of-life stack than the level we’re talking at right now), I think it’s a fundamentally sterile perspective. Without a sense of “other”, happiness is boring — there’s no appeal to me thinking in terms of just my own experience. Also, happiness is finite: you only have so many instants of experience in your life, and as soon as each one is gone, it’s gone for good. You can remember it, but all memory is is just another instant. There’s no flavor of the infinite, no transcendence when you think in terms of happiness, and when you narrow yourself to the limited range of human experience over a finite time span, that too induces, at least in me, the feeling of sterility.

So happiness doesn’t help me sort out what context I want to adopt, although it certainly motivates thinking about the question. At the end of the day, I think any of the contexts above can make someone genuinely “happy”, however you want to define happiness, if they’re adopted sincerely. The thing I’m looking for, though, is something to help me think that one of the contexts is right, because as long as I can ask the question “why is this right?” and not come up with a good answer, it undermines my sincerity when I try to adopt one. Right doesn’t have to be an absolute truth, to be clear. A “practical” right is fine with me too, and there’s nothing structurally unsound in saying that one is right because it makes me happy… the problem I have with that argument is simply that “happiness” isn’t a criterion that moves me strongly enough.

I was thinking about all of this yesterday, and the answer that popped into my head was “gift”: rather than seeing the meta-goal of life as happiness, see the meta-goal of life as “giving”. I’m not sure I can completely intellectually defend that as answer, but when it came to me it felt very right, so I want to play with it for a bit and see where it gets me.

Immediately, thinking in terms of giving breaks me out of the sterility of happiness. A “giving” universe is not solipsistic, nor is it blandly monist. Rather, there is an I and a thou, a giver and a receiver. Moreover, it’s not just a duality (always an intellectually suspect condition): the giver can be the gift, the receiver can be oneself: identity can ebb and flow, merge and separate. The essence of giving is a dynamic, a motion, an aliveness. Along the time dimension, giving is a verb, whereas happiness is a state. The duration of a gift can be instantaneous or infinite, finite or unbounded. So as a basic thing-to-want-out-of-life, the notion of giving immediately feels more right to me than happiness, even though functionally there is overlap (since “to give is to receive”).

The next question is how “giving” relates to the original contexts that I’ve been trying to decide between. At first blush, it seems more fundamental, which is what you’d want. You can ask “Why create art?” and answer “to give of yourself to creation.” You can also ask, “why evolve, why strive to improve yourself?” and again answer “to give of yourself to creation.” Same goes for the heroic and the rational modes, and as for the spiritual, I think “giving” is really a certain way of cashing out what spiritually really means, a way that happens to be, in my opinion, a really good one.

Does it favor one over the other? Not really, but I’m okay with that: I wasn’t hoping for a knock down victory of one context over the other. I’m satisfied with a basic meta-context in which the varied modes can be justified, played off against each other, merged and recombined. It makes an impossible problem to solve into a merely difficult one, one that I think can be resolved on the level of day-to-day choices about where you spend your time. Getting to that point — the point where the big questions in life are best solved by just living — is great victory. I suppose you can get there by not asking the questions to begin with, but asking and answering and then being able to move forward for a time without their burden is really worth something, at least as far as I’m concerned.

Related link: http://www.paulgraham.com/makersschedule.html